|

|

||||

|

|

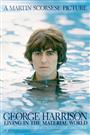

by Donald Levit  Cherubic Paul and cutting John had their fanatic partisans, and homelier Ringo behind the three guitars had those who thought him cute. Now director-producer Martin Scorsese’s George Harrison: Living in the Material World would demonstrate that this fourth, quiet Beatle’s still waters ran deep. Premičring at Telluride, selected for the New York Film Festival, and titled from a 1973 album, the three-and-a-third hours is divided into two parts, for a number of separate days on HBO and HBO2 television. Some footage revealed for the first time, the documentary includes interviews with name survivors among the world of pop music and culture, spiritual teachers, friends, and family from a Liverpool childhood up to twenty-three-year-old son Dhani and widow Olivia Arias, plus Harrison himself up to a comment on the earliest stages of the cancer that killed him ten years ago. All coincide on the fine person the lead guitarist-songwriter-filmmaker-philanthropist-seeker was, even over Olivia’s “good and bad and loving and angry and everything.” In the rush to neat partition of the life into contrary pulls of things of this world and nirvana of the other, the Fab Four split is soft-pedaled from the usual accounts of acrimony. Klaus Voorman’s bringing up a “stepped back very heavily into drugs” is not followed up on, and two embarrassing lawsuits are not mentioned: one successful, for “My Sweet Lord” “unknowingly” plagiarizing the Chiffons-Ronald Mack “He’s So Fine,” and the ugly out-of-court-settled posthumous case against oncologist Dr. Lederman. Ringo’s account of their final meeting and his dying friend’s humor and humanity points to death in Among interviewees credited as “contributors” is Yoko Ono, reviled by some as the Dragon Lady of the Beatles’ demise. But we learn that the time had just come, that she was not the instrument. Paul, Ringo and others praise George’s songwriting, and they, he and others realized that against the Lennon-McCartney team, it was impossible for him to get his own compositions shoehorned in and that he was ready to strike out on his own. Global Beatlemania is glimpsed through archival material. The frenzy isolated the four friends confined to police guards, chauffeured cars and hotel rooms, and though the lads loved one another to this day, such proximity spawned tensions. Unlimited money, things and women by their early twenties was as much curse as blessing, and “we still lacked something.” The core of this telling is the living in that material world, contrasted with Harrison’s search for the spiritual non-material, which he found in the religion, philosophy, music and culture of the Indian subcontinent and to which he introduced his mates and the world. In doing so, and in the Bangladeshi cause which he espoused in rock’s first charity megaconcert happening, he shied from the flower power of a scary Hashbury whose potential for violence came out at Altamont Speedway. Itself termed “a journey,” the documentary does evidence the subject’s individual journey towards peace and understanding. There is unintended irony in all this talk about simplifying while George and company frolic in To ill-starred John, “George himself is no mystery” but an “immense” inside complexity. Therein lies the problem. In the same runtime, Scorsese showcased an equally personally private Dylan’s more absorbing metamorphoses and personae in No Direction Home. Denying that he had become a recluse, (Released by HBO Documentary Films; not rated by MPAA.) |

||

|

© 2024 - ReelTalk Movie Reviews Website designed by Dot Pitch Studios, LLC |