|

|

||||

|

|

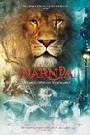

by Jeffrey Chen  As many readers already know, there are two ways to approach The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (hereafter Narnia). The first is as a plain-faced fantasy, in which a group of kids are stranded in a magical land of talking animals, mythical creatures, and the forces of magic. The second involves seeing it as the Christian allegory it truly is, a story that manages to feature betrayal, sacrifice, and resurrection. Much criticism and analysis already exists about that aspect of the books by C.S. Lewis, and it's a topic still relevant, thanks to the release of this movie (in the latest news, churches are organizing group viewings of the movie for the kiddies). Is it of interest, however, to separate the two approaches in a discussion of the movie? I might say only in one respect -- the books and, thus, the movie are aimed at children, and children are not likely to draw Christian parallels from a film that features colorful visual effects, a wide range of characters, and new lands to explore. Therefore, one has some room to talk about it as a pure work of fantasy, and yet this is where Narnia falters. As a story, it's surprisingly shallow because it's so intent on sticking to its agenda that character believability -- possibly more important in fantasies than in other genres since it provides the only real grounding -- suffers as a result. To watch Narnia is to observe a promise of rich fantasy ultimately hampered by its insistence on delivering a very specific, pre-defined story simply dressed up in ornate clothing. It begins with a brood of four children who are sent away to live with a reclusive professor, away from the dangers of war in their homeland. Their personalities are lightly drawn, and they eventually happen upon a portal to a magical world. The potential for story here is most ripe. However, once the tale begins to develop, the main characters take a backseat to arbitrary events. They become ciphers the minute someone explains that they are prophesied to rule the land -- they no longer make stuff happen, stuff just happens to them. This is most true of the two oldest siblings, Peter (William Moseley) and Susan (Anna Popplewell) -- Peter, the de facto head of the group, has little personality, and Susan is there mainly to give Peter a counterpoint. Lucy (Georgie Henley), the youngest of the bunch, appears perhaps the most developed in terms of character -- she finds Narnia first and has her honesty questioned when she reports about it. However, the most blatant use of a character as a device comes from Edmund (Skandar Keynes), a sour, rebellious type who creates most of the trouble when he stumbles into Narnia and happens upon the White Witch (Tilda Swinton). He's portrayed as a rotten apple who commits the atrocious act of endangering his siblings, and, frankly, isn't given any kind of a chance at showing some redeeming value (save for a constant look of guilt after he's realized what he's done). Edmund is there to teach the audience a lesson -- if you don't do as you're told, you'll be punished. That, of course, is the most basic interpretation. When the deeper view is brought in, it becomes obvious that Edmund stands in for sinners, and that the means toward his redemption are out of his own hands (instead, they're in the hands of a savior character). In every way, he's no longer a character in his own right, just as the other children begin to function as receptacles for other lessons to be delivered involving authority, divine right, sacrifice, and war. The fantasy no longer exists as a self-supporting, character-driven story -- it actually feels heavy with the air of adult machinery. Narnia disguises itself well, however, with its computer-generated effects and a bright, shiny feel. If the movie is meant as fantastic entertainment first and religious messenger second, it would mostly achieve that goal mainly because it overplays its visual environment and scale. But the film doesn't feel as magical as it could've been, not only because it becomes clear the fantasy aspect is merely a vehicle for another purpose, but also because it underdevelops character motives as a result. There is where the true magic would lie. (Released by Buena Vista Pictures and related "PG" for battle sequences and frightening moments.) Review also posted at www.windowtothemovies.com. |

||

|

© 2025 - ReelTalk Movie Reviews Website designed by Dot Pitch Studios, LLC |