|

|

||||

|

|

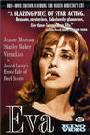

by Donald Levit  Still box office, Old Scratch has evolved over the years. When not cartoonish special-effects bogeyman, the Adversary may now also choose an urbane, well-mannered guise, impeccably ironic as De Niro, Pacino, Gabriel Byrne or Eriq LaSalle, to do battle with modern priests or suits in Jason Miller, Keanu Reeves, turncoat Byrne, even a muscular California governor. Though Kevin Smith cast Dogma's God as a woman and Alberto Movaria's Devil consciously and often assumes seductive nymphet form, hardly anyone envisions an actual femme fatale screen Lucifer. Then again, who needs to? Forty-two years ago, exiled American Joseph Losey gave cinema definitive evil in Eve/Eva. Not the easy horned, brimstone-breathing version of goatish tradition, but the calculating, unfeeling and amoral title lady personified by hellishly beautiful Jeanne Moreau at her best. The honoree of "Stranger on the Prowl," the Film Society of Lincoln Center's twenty-nine film May retrospective, the Wisconsin-born director is himself an interesting figure who came late to features from a background in theater and book reviewing, radio, stage production, directing and managing --Radio City's first live stage show -- and documentaries for the Rockefeller Foundation as well a petroleum company. An edgy maverick whose early Hollywood movies already pointed to social concerns and a European feel, he delayed a 1951 appearance before HUAC in order to finish shooting in Italy and was blacklisted; for the next quarter-century he worked in England (his name omitted in U.S. distribution credits) and then continued in France. Known for anti-fascist social and class commentary, and for fruitful collaboration with playwright Harold Pinter -- who has a rôle as a television producer in Accident -- Losey is less generally remembered as the master he was of baroque ambientation and psychological probing. Rudely cut from a hundred fifty-five minutes by producers Raymond and Robert Hakim prior to release, to result in what Losey felt "a common tawdry, little melodrama," the present, partially reconstituted Eve is one of at least two extant versions, neither without its shortcomings in continuity and celluloid quality, including difficult white-on-white Finnish and Swedish subtitles (and some dialogue is in Italian, a little in French). Awkwardly framed as flashback retelling -- one forgets the "present" until reminded at the end -- against an unnecessary Adam-and-Eve corner relief-voiced commentary, the film is slow to reveal who is who and what the relationships are. But once Gianni Di Venanzo and an uncredited Henri Decaë's shadowed cinematography has snared us, this adaptation of a 1945 James Hadley Chase novel moves with serpent grace. Welsh novelist Tyvian Jones (Stanley Baker) is the toast of Continental Beautiful People. Engaged to Francesca (Virna Lisi), secretary to artists' agent Branco (Giorgio Albertazzi) who also loves her and suspects Jones, the writer is an unapologetic womanizer "from six to sixty" and, it will out, a haunted fraud as a writer. Amid the barren pessimism that also marked Antonioni's trilogy of those years, and emanating the dark sexuality of early-Bond Sean Connery, Jones falls to Eve, an available sensual delight with a husband conveniently building African dams. Mysterious and calculating, the temptress springs from nowhere that can be pinned down: her sincere-faced tale of a married neighbor's advances to her at eleven, orphaned with a tubercular sister, concludes with a laughed "You'll believe anything!" Dating from a chance meeting at his country home, when he throws out her male companion, he is sucked into the quicksand. Her lust for money and luxury is unsullied by physical desire, although Francesca's bathside photograph appears to spur an additional hunger for mischievous power, and the following year, in The Servant Losey would again explore the depths of personality domination. A tar baby, the non-drinking but increasingly drunk Jones's obsession is beyond sex, as the object of it leaves but does not quite leave, with tragic consequences. Venice is suitably sinister in inner decadence behind crumbling exteriors and narrow angled alleys, phallic towers and living canals, an inferno of damp winter ruins rather than sightseers and carnival hearts. Smoldering, chain-smoking, Moreau is master, even to the brief closing frame. There is no moral or justice or awareness. Obsession is possession, and has no ending. The blared blah Michel Legrand score is a detriment, but even though Losey's intended Miles Davis background was scotched, Billie Holiday's recurrent "Willow Weep for Me" and "Love Oh Love Oh Loveless Love" are a haunting fit. Jones's wildly successful novel is translated as L'etranger en enfer, anticipating the non-U.S./U.K. release title of Eva, the Devil's Woman. Dietrich's Lola-Lola Frohlich, Bette Davis' Mildred Rogers, Moreau's Eve, all give the lie to Nietzsche's aphorism and Vadim's frolic; God was not the creator of such women. (Released by Times Film Corporation; not rated by MPAA.) |

||

|

© 2026 - ReelTalk Movie Reviews Website designed by Dot Pitch Studios, LLC |