|

|

||||

|

|

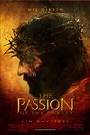

by Diana Saenger  How many people have not heard about Mel Gibson's The Passion of the Christ by now? I'll wager only a few. For this highly anticipated film, Gibson served as both producer and director. He also collaborated with screenwriter Benedict Fitzgerald to write his version of Jesus' last 12 hours on Earth as taken from the Books of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John in the Bible. Like the Trinity -- Father, Son and Holy Ghost -- The Passion of the Christ incorporates three closely related links. It's a film; it's a much-hyped marketing event; and it's rapidly becoming the newest handout on religious belief. Dissecting the movie's spiritual layers will be done, I'm sure, by religious scholars; my comments concern only the filmmaking aspects of Gibson's movie. Gibson says that nearly 12 years ago he found himself in spiritual crisis and began searching for answers. However, he's not the first director to make a film about Jesus' death. Cecil B. DeMille's King of Kings (1927) and Martin Scorese's The Last Temptation of Christ (1988) come immediately to mind. Nevertheless, The Passion of the Christ is like no other film dealing with this topic. Gibson bypasses the need to actually tell the story of Jesus' death, as billions of people have read, debated and preached about it for almost two thousand years. What Gibson goes for instead, is an emotional awaking to what he believes really happened -- and he does a commendable job in presenting his theories. "My intention for this film was to create a lasting work of art and to stimulate serious thought and reflection among diverse audiences of all backgrounds," said Gibson. An accomplished director (Oscar-winner for Braveheart), Gibson tells his story through the emotional arcs of the characters -- mainly Jesus (Jim Caviezel) and his mother (Maia Morgenstern). Renowned cinematographer and four-time Oscar nominee Caleb Deschanel superbly captures Gibson's vision of the film. Long, close shots of Jesus, even during the most brutal beating scenes, reflect a peacefulness and understanding in Caviezel's eyes. Likewise, in shots of Morgenstern (Mary), her expressions reveal that although she understands this is Jesus' destiny, she is his mother and cannot conceal her agony. Every moment of her son's torture is hers as well. Monica Bellucci (Mary Magdalene), Mattia Sbragia (the High Priest, Caiphas) and Hristo Naumov (Pontius Pilate), all fine actors in their own countries, also benefit from great camera work and direction. They project every ounce of their emotions and motivation, not through their dialogue, but in their facial expressions. Because Gibson uses the camera, settings and mood to tell the story, he includes very little dialogue in this film. The lines are spoken in Aramaic by the Jews and in Italian by the Romans. Gibson wanted Jesus to speak the language he would have spoken nearly 2,000 years ago. Personally, I found that aspect mildly distracting, and I don't think it added anything to the believability of the film. I also wonder why Gibson used subtitles if he's so intent on getting the message of Christ to the public. As a filmmaker, he knows that mainstream moviegoers usually dislike subtitles. Forcing viewers to read while watching the film takes away from the mood and expression of the story for many of us. Not everyone can process all this swiftly enough to appreciate fully what's happening on screen. Actor Jim Caviezel (The Count of Monte Cristo) takes on the role of a lifetime with his portrayal of Jesus. He may be the only current actor who could have carried off this role successfully. Already a religious man, Caviezel conversed at length with Gibson about the pros and cons of playing Jesus. Still, how could he foresee the sacrifices he would ultimately make? He endured seven-hour daily make-up sessions, had to learn Aramaic, suffered frostbite from filming in a loin cloth as well as burns on his feet from a heater placed beneath the cross, had a back injury, dislocated his shoulder and was struck by lightning. "But if I hadn't gone thought all of that, the suffering would never have been authentic," said Caviezel, "so it had to be done." Many comments by those who have seen the film address its violence. The majority of the scenes are filled with savage beatings and spurting blood, juxtaposed with laughing, clueless men who carry out their orders all too well. "I really wanted to express the hugeness of the sacrifice, as well as the horror of it," Gibson said. So does Gibson get his message across? Yes and no. Several scenes transform an idea from possibility to Hollywood-ness. Consider the insertion of the "Satan" figure, a women (Rosalinda Celantano) with the voice of a man who shape-shifts throughout the film, causing comments such as "another Gollum" to surface. And, because Gibson wanted Evil to be about, "taking something good and twisting it a little bit," he includes some strange scenes with a weird looking baby that just don't work. In general, The Passion of the Christ effectively conveys Gibson's religious convictions. "It's ultimately a story of faith, hope and love," he says. I agree. However, it takes a lot of wincing to watch Gibson's version of this powerful story. (Released by Newmarket Films and rated "R" for sequences of graphic violence.)

|

||

|

© 2026 - ReelTalk Movie Reviews Website designed by Dot Pitch Studios, LLC |