|

|

||||

|

|

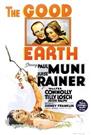

by Donald Levit  Pearl S. Buck was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1938, seven years after the Pulitzer for The Good Earth, first of The House of Earth trilogy. Coming back into her own recently, the authoress never recaptured the enormous popularity of that volume, her later life, social consciousness and political stance -- notably advocacy of dictator Chiang Kai-shek -- contributing to her eclipse. Subsequently forgotten, too, was Louise Rainer, the first performer, and for thirty more years the only actress, to take home consecutive lead Oscars, for The Great Ziegfeld and in 1937 for The Good Earth. (She died fourteen months ago, less than two weeks shy of her 105th birthday.) Thereby hangs a tale beyond any judgement on the latter film, about which opinion is generally though far from unanimously enthusiastic. On Clay Street, San Francisco, the Chinese Historical Society of America Museum documents the Sinophobia that reigned for at least a hundred years from the Transcontinental Railroad on, when public prejudice, cinema codes, and national and California anti-miscegenation laws dictated that Caucasian actors play Orientals (as well as Afro- and Native-Americans). Swedish Warner Orland, New Yorker Richard “The Yellow Man” Barthelmess, Hungarian Peter Lorre, and “eternal Chinese in drag” Montanan Myrna Loy were preferred. Los Angeles’ own third-generation Chinese-American Anna Mae Wong was rejected for the O-Lan part she coveted and so then turned down that of venal courtesan Lotus Blossom as another “screen Chinese always the villain. And so crude -- murderous, treacherous, a snake in the grass.” Producer Irving Thalberg died suddenly, and the film was dedicated to him, but at his insistence Austrian-born Jews Rainer (some accounts have her as German, belying her nickname of “the Viennese teardrop”) and Paul Muni had been cast as leads O-Lan and her husband Wang Lung, with Charley Grapewin as the latter’s father, Walter Connolly as loveable rascal Uncle, and also-Austrian Tilly Losch as concubine-second wife Lotus Blossom. And so on down the line. Today O-Lan’s unquestioning subservience is equally unacceptable as that casting, though it is fair to note that Asian films as well, e.g. The Story of the Last Chrysanthemum from Japan, are at least as accepting of female acquiescence to male domination. Her quiescence, rather humiliation, is so profound that even the self-absorbed obtuse husband remarks at her proud few-sentence assertion of motherhood (of a son, of course), “I haven’t heard you speak so many words since you came to this house.” Embodying supposed peasant stoicism and Confucian “the benevolent are still,” neither Rainer nor Muni vary facial expressions during the whole two hours eight minutes. Still, the film is moving, even with original director George W. Hill’s suicide, substitute Victor Fleming’s debilitating illness, and final choice Sidney Franklin’s pedestrian finishing up the four-year project. Returning to cinematography after directing six features on his own, Karl Freund won the Oscar for his striking b&w contrasting of the sparsely populated early and late rural northern locations and drought migration columns with the southern city crush of humanity in the middle, culminating in revolution, frenzy, rioting, looting and military executions. Of special note, too, are the Arnold Gillespie-Slavko Vorkapich effects for the wind-borne plague of locusts, their device of swirling coffee grounds in water more exciting than today’s facile false CGI stuff. SPOILER ALERT A slave in the elegant Big House which represents aspiration, O-Lan is grateful to be bought as wife to farmer Wang and bears him four children, one of whom dies at birth, either naturally or arguable stifled by her after its first cry in that time of famine and looming starvation. She cooks, mends, works in the fields, saves money to buy more slivers of land, silently accepts his late philandering and lies, fades willingly into the woodwork, comes seconds away from a firing squad in being the source of the family’s financial redemption, and survives long enough to bless their first son’s bride and in turn be blessed by contrite Wang: “O-Lan, you are the earth.” In source novel and film, simplicity, family, and hard work are the pillars. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer press releases touted “something of the soul of China,” a California concept of that, of course. Buck had grown up there, and her Swedish Academy speech highlighted “land, peace, children,” less an introduction to the Occident of Chinese otherness than an iteration of universal dreams. (Released by MGM; not rated by MPAA.) |

||

|

© 2026 - ReelTalk Movie Reviews Website designed by Dot Pitch Studios, LLC |