|

|

||||

|

|

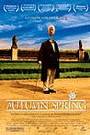

by Donald Levit  A uniquely sensitive twenty-something-year-old might not be bored by Autumn Spring, but viewers a decade or two nearer the grave and slightly more aware of mortality may appreciate it more. And those well past the half-century mark will take this film to heart. For it is our own, a wry tender embrace of ageing and loving, dying and living, to the fullest, as best one can. Facing Soviet troops and tanks in August 1968, the "Prague Spring" of commercial and critical success for Czechoslovakia's "new wave" collapsed into hard times. Young directors and actors deserted the industry, often the country. Although sporadic flashes have not revived the nation's cinema, this multiple award-winner from documentary/feature/screenwriter veteran Vladimír Michálek goes far toward restoring lost prestige. Prague is inviting, and this sad comedy emerges as winning even though stretched in places. However, it's the actors who bear it home. The performance of Vlastimil Brodský is especially noteworthy, beyond the moving footnote that, rather than slow decline, this already ill internationally known actor chose suicide shortly after completing this work. His "Fanda" Hána is a man of not many words and gestures, but the jowly, beagle-eyed face expresses the human condition with the genial economy of a Fernandel. As he and old theatrical partner Eda Stára (Stanislav Zindulka) roam the city and nearby countryside assuming different outrageous rôles, it is obvious that "chemistry" need not be restricted to a mixed-gender couple. Magic, too, between Brodský and his platonic actress friend of fifty-five years, Stella Zázvorková. She is Emílie, the suffering wife who keeps money in labeled tins, squabbling with Fanda about his refusal to be serious, plan for the future or save money (now for their funerals). She reasons that they should relocate to senior housing, leaving son Jára (Ondrej Vetchy) their flat to solve his problems with a current wife, two exes and numerous children. Fanda puts his foot down -- "even divorced ten more times, nobody gets me out alive" -- and he and Eda continue their hilarious escapades, as Metropolitan Opera maestro and secretary looking to buy a country estate; as Himalayan mountaineers, wedding gate-crashers or subway inspectors who accept girls' kisses in lieu of tickets; as television crew to record a ritzy casino, or movie stars in need of flowers and tap-dance classes. Not as social protest to "show the nouveau riche lumpenbourgeoisie," but with mischievous boys' faces to "make fun of death." Their hearts are generous, for newspapers are returned (with the crosswords done); a poor actress is visited on her eighty-fifth birthday and 2,000 crowns left under a wine bottle; a man fooled at the cemetery gets cash for a funeral wreath; a young wife is shielded from her jealous husband and a fake blind beggar who bolts with their money absolved. What might have been seen as second childhood is presented as but a continuation of child-like pleasure in spontaneous possibilities. Irresponsibility, however, can go beyond the bounds, out into deep water, and a last "nasty trick" brings Emílie to despair and, indirectly, Eda to the hospital. Before a judge, the wife's and son's indignation melts in love, and although Fanda promises to reform and even stop smoking, life will not be the same, nor, for that matter, will death. Avoiding gimmicks, depending on the faces of a few gifted actors and brief situations which appear improbable but are not, rounded by a rewarding conclusion, Autumn Spring celebrates age and love and joy better than that syrupy family affair, On Golden Pond. This Czech film has, of course, its holes -- why, for example, a crisis after forty-four years of marriage? -- but to dwell on them is silly in the face of such tender quality. (Released by First Look Pictures and rated "PG-13" for language.) |

||

|

© 2026 - ReelTalk Movie Reviews Website designed by Dot Pitch Studios, LLC |