|

|

||||

|

|

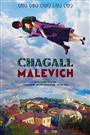

by Donald Levit  Marc Zakharovich Chagall lived long in fame, Kazimir Malevich died forty years younger and is familiar only in reduced circles; Shalom Aleichem is recognized as a greeting rather than the Yiddish writer originally Rabinowich. Yet the three are gathered, mythologized, in Chagall-Malevich, veteran director-writer Alexander Mitta’s first film in a decade. The unmentioned Aleichem connection lies in the setting out of Tevye the Dairyman through Fiddler on the Roof, the shtetl in the western Russia Pale of Settlement, from which dreams, fantasy and religion are Chagall’s artistic and emotional release. Airborne-awe final moments like those of Inárritu’s Birdman or (the Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance and a fact-fantasy mix like that in Sfar’s Gainsborough: A Heroic Life lead one to question how loose the hundred sixteen minutes plays with history beyond the bare skeleton. “We don’t write history, we create myth,” affirms Mitta, citing as evidence Tolstoy’s poetic license with Napoleon. Born to his own voiceover during a fire not specifically attributed to pogroms which ravage Jewish Vitebsk (Vitsyebsk), Chagall later moves to the heady art scene of pre-World War I Paris, where aspirants experiment, live to the fullest on little money, and share beds, studios, techniques and lovers. They fête him on his birthday and offer a naked woman as gift, but the impossibly beautiful and idealistic birthday boy (Leonid Bichevin) is saving his virginity for Bella Rosenfeld (debutante Kristina Schneidermann), the girl he left behind. Nothing is shown of his “immense success” in France, even harder to believe in, given that her father objects to him back home in the village. But the lady immediately drops poet-suitor Naum (Semyon Shkalikov) into his first of two river plunges. At the happy couple’s Jewish wedding the latter broods that his true bride is the Revolution, anyway, in consequence of which he will rise to the post of local Commissar. He then drafts unworldly friend Chagall, who in all innocence opens the Academy of Modern Art in the large house seized from a pathetic elderly bourgeois couple denied even a bedroom. Students flock to his school, including the son (Lyova, played by Yakov Levda Zheleznyak) of disapproving Rabbi Itzak (Dmitry Astrakhan) and starry-eyed girls like Sonya who fall in love with their teacher-founder. Though a holstered pistol is forced on him, the curly-haired artist is oblivious to everything mundane, political or practical. The real-life artist’s granddaughter and Chagall Committee in Paris gave their approval, allowing almost a hundred and forty of his (and Malevich’s) paintings to be filmed, so perhaps he was indeed so removed from it all. The problem, as the director saw it and according to him the reason no previous such “cultural event” film was made, is that audiences want “entertainment,” the conflict which “the dreamer, almost blissful” subject does not bring into play. Enter Malevich, manly handsome as opposed to the other’s boyish model features. Brought in as an additional teacher, the newcomer polarizes students and staff with uncompromising insistence on Suprematism, bright bare monochromatic geometric shapes not to be frozen apart from life in deadening museums. Naum cannot resist groping and trying to blackmail old flame Bella, revolution sweeps the land, Trotsky passes through on a pastel blue train, and oblivious to it all Chagall paints flying peasants and animals on canvases and fences while the town turns, or is turned, against him. There is some schmaltz but, apart from wedding moments, not much Old Country here. And the value of art at such times when “life isn’t worth anything” gets lost in the shuffle. Flatness will put off those not intrigued by the mix of approaches. Too bad, because the ending does pleasingly bring together those disparate poles and at the same time allows each of the opposites to live and let live. (Released by Shi-Film, LLC; not rated by MPAA.) |

||

|

© 2026 - ReelTalk Movie Reviews Website designed by Dot Pitch Studios, LLC |