|

|

||||

|

|

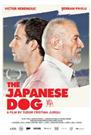

by Donald Levit  Bucharest’s submission for foreign-language-film Oscar, The Japanese Dog/Câinele Japonez proved so embraced at the Edinburgh International Film Festival and the 2014 edition of the Museum of Modern Art-Film Society of Lincoln Center annual New Directors/New Films, that MoMA brings it back now for a full week. It seems that just about every country has its “New Wave,” though there is enough in common among recent productions from a couple in Eastern Europe to tempt speaking of an “Ex-Soviet Bloc New Wave.” Fans attuned to Romania’s will be advised that this début from director/co-writer (with Ioan Antoci)/producer Tudor Cristian Jurgiu is sad and joyful and quiet and humorous but not in the macabre gallows whimsy vein of The Death of Mr. Lazarescu. Its calm background-noise celebration of rural nature is like that of Hungarian Hukkle, though here deaths are not understandable murders but the results of an act of God and have occurred before pre-opening-credits villagers salvaging what they can from still soaked lowlands. Integral to the total are un-flamboyant shots throughout, of stark symmetry through doorways or windows, of sloped fields with solitary human figures against the sky, of Dutch Master-ly interiors sidelit from a single source. As with the off-screen barks, tweets, cheeps, chirps, neighs and brays, unnoticed but essential to the whole, the tale itself might at first appear so negligible as to be non-existent --parallels have been remarked to the works of Yasujiro Ozu -- until one sees that life is indeed here, tender and flatline as it most always turns out. Complications arise, not in Nature, unpredictable and uncontrollable and so to be accepted as such, but from human reactions and misunderstanding, irrational and to be resolved by those involved. Stage and screen veteran Victor Rebengiuc plays Costache, first framed through a ruined doorway and then a window, picking items from the rubble of what was his house, to wheel them to the schoolroom and later the other house temporarily supplied by town hall. He has lost most everything, including wife Maria, in the flood. Neither bitter nor defiant, he goes about setting up again, insisting on paying -- only not too much -- for outside help. Neighbor Tata Leanca (Alexandrina Halic) helps out over his objections, asking a “thank you” as sole return for milk or food refused or not. Mr. Costache also refuses to be hurried into the electric company director’s proposal to buy his land and ruined house. He has no bank account but concern about robbery of the offered two hundred fifty million lei is no more than an excuse, but neither is the episode a criticism of greedy real estate developers -- there are no villains here, just different opinions. Small towns abound in rumors, but true news travels equally fast and anticipates the return of his estranged son. Ticu (Serban Pavlu) drives from the city with wife Hiroko (Kana Hashimoto), his language teacher during his first years away in Tokyo, and their son Paul Koji, who like his mother speaks Japanese and pidgin Romanian -- “I have seven [years].” From the outset some unresolved issue between father and son is patent, but the older man is charmed by his grandson, who reacts in kind and, in the end, leaves the cementing gift of the title’s unintelligible-English-speaking toy pooch. Expectation might lead to an assumption that these eighty-six minutes will move towards cliché drama, or even tragedy, as they uncover the roots of Ticu’s smothered anger and Costache’s guardedness. A pleasant surprise is that, as gracefully as “jilted” local lass Gabi (Ioana Abur) puts aside the past and false pride, as innocently as “Koji baby” bridges “samurai daddy” and grandpa, as quickly as Danila and pouting Costache down schnapps while clarifying a long-ago scuffle, the inevitable is accepted, tenderly, in love, and without hitting us over the head. Through a windscreen, a small smile. Life is like that, or should be if it is not. |

||

|

© 2026 - ReelTalk Movie Reviews Website designed by Dot Pitch Studios, LLC |