|

|

||||

|

|

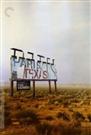

by Donald Levit  The Museum of Modern Art recognized Wim Wenders’ The Salt of the Earth among “The [Oscar] Contenders” and now again in a sold-out, stand-by-waiting-line series with the director introducing and/or commenting on the first weeks’ showings. Titles among the twenty features and several shorts resonate with place names, geographical designations and travel, and kicking off the essential survey, just shy of two-hours-and-a-half Paris, Texas garnered raves from its 1984 beginning and just as strong negatives as being self-satisfied and, like others of Sam Shepard’s stage- and screen-plays (this one with L.M. Kit Carson), molasses slow. There is a visual starkness about much of the director’s fiction and, especially of late, documentary work. As with Sergio Leone, the German soaked up Americana and captures our national psyche as well as almost anyone, even to music. Here, the Ry Cooder (connected with Wenders in Buena Vista Social Club) slide guitar adds much to landscape and mood. Revolving about family reunions, in the plural, the per se plot is not out of this world, and the wrapping up of whatever mystery is less laudable for what is revealed than for how it is managed. The dénouement perhaps surprises but, given the direction of society in recent years, seems neither impossible nor exaggerated. The acting, Robby Müller cinematography, music and tone carry the day after pinstripe-suited baseball-capped Travis Henderson (Harry Dean Stanton) wanders back in from four years in the Mexican desert, not to the Promised Land but a Southwest filling station that seeks payment for a suspect doctor’s opinions (Bernhard Wicki) and phoning the dehydrated silent man’s brother in L.A. Signboard success Walt (Dean Stockwell) rushes from the coast to gather his spacey given-up-for-dead sibling, only to find him flown but easily traced again and uncommunicative, as empty as the wide-open spaces around them. Travis had up and disappeared, leaving behind a much younger wife and son. Psychologically unprepared to care for the three-year-old, Jane (Nastassja Kinski, twenty-four, to Stanton’s fifty-eight) deposited him with Walt and his wife Anne (Aurore Clément), childless themselves but grown to consider the now eight-year-old Hunter (Hunter Carson) their own, while his birth mother dropped from sight and from communication although making monthly deposits for the boy in a Houston drive-through bank. At first letting out little more than that he once purchased a desolate lot in nowhere Paris, Texas, and later that his and Walt’s father cracked endless jokes about their mother’s being from Paris . . ., the returnee oddball is awkward with the son who avoids him and clings to the couple who have raised him. A projected Super 8 home movie shows Jane for the first time and the love-light in her and Travis’ eyes; so, soon a nifty cinema play of developing father-son walks back from Hunter’s school, images their thawing relationship. Here and there, bits and pieces emerge, about the once-family of three and its breakup. The precise series of events remain fuzzy, until Travis’ intercom phone monologue in the dark booth of a girlie club. Father and son are together at the boy’s request as they set off on what could have been no more than your run-of-the-mill road movie; but these Kings of the Road seek to find a wife and mother. For no reason but the fun of it, in a beat-up baby-blue Ranchero pickup they are made to stop at Ranchero Motel on the way, finally parking beside a baby-blue cinderblock wall painted with a looming Statue of Liberty which has Kinski’s eyes and lush lips. What is happening throughout is little, and almost entirely internal, with no action. Aside from the three -- or five -- involved, the world does not notice, and there is no edge-of-your-seat suspense. Love and suffering just go together, like a horse and carriage. Good intentions, and sacrifice, may make it rewarding, at least for two or three of the five. (Released by 20th Century Fox and rated "R" by MPAA.) |

||

|

© 2026 - ReelTalk Movie Reviews Website designed by Dot Pitch Studios, LLC |