|

|

||||

|

|

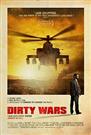

by Donald Levit  Following a private screening of Oscar candidate Dirty Wars, director Richard Rowley and uniting thread film participant and co-writer Jeremy Scahill kidded seriously about being amazed and a bit in awe over rubbing elbows with the famous at a glitzy reception for contenders. They also indicated the financial difficulties of startup work on their own, even if audience questions were about politics and not at all on filmmaking processes. Investigative reporter Scahill did a seven-hundred-page book of the same title, subheaded The World Is a Battlefield, while making this documentary. He pointed out current media cutting back on on-site coverage, on account of interests, pressures, costs and, though he was cool at the moment, real and present dangers. Governments have taken to embedding operatives as ostensible journalists, and it does not need recalling the gratuitous fate of Gene Hackman in Under Fire to shudder watching him (and crew) on-screen alongside, say, warlords and soldiers in the Horn of Africa. Location-shot in a few hot-spot countries, plus clips from Power Broker capitals, this quest for truth begins on a road that must be retraced before sundown because “the Taliban own the night.” The bearded Wisconsinite listens to the Afghan patriarch and survivors of a family decimated by unidentified intruders who sounded American. Without warning or warrant to look for terrorists, the burly assassins had broken into a rural family gathering and left behind dead and dying that included children and two pregnant women but took care to remove anything that might identify them, even manually digging bullets from bodies and walls. Attempting to trace the night-raid perpetrators, the slightly less than ninety minutes uncovers, among other things, an unsupervised and at that time totally unknown government organization that, rationalized by the “War on Terror,” has acquired immense independent power. In the process it has changed the rules of the game, resulting in mounting collateral damage, in the use of drones and, much emphasized among extralegal abuses covered, in the kill-list targeting of American citizen Anwar al-Alwaki and, days later, his sixteen-year-old son, “deprived of life . . . without due process of law.” The Muslim cleric had gone from all-American boy to radicalized preacher as a result of America’s domestic as well as international reaction to 9/11 and to his own seventeen-month solitary confinement. With too much footage of pushpins, keyboards and such, the documentary takes the crew on to Yemen, Iraq, Kenya and Somalia. But it also bores homeward to Brooklyn and to Washington, television talk shows more concerned with wisecracks and personalities than deaths overseas, to government officials and hearings, leakers with obscured faces, to the military, SEALs, and decorated Vice-Admiral William McRaven and his Joint Special Operations Command or JSOC out of James Bond run amok. To “find, fix and finish” humans labeled enemies or potential threats, these global ops are responsible only to themselves and not held accountable to the American people and almost none of their elected representatives. They constitute a law unto themselves, beyond the law of the land akin to the soldiers of fortune brought to light by Scahill in earlier Blackwater: The Rise of the World’s Most Powerful Mercenary Army. Although during the Q&A it was affirmed that things have gotten worse rather than improved since January 2009, Present Obama only appears twice, in archival frames, and the documentary is at least in theory non-political and not intended as overview of the past thirteen years. Instead, the filmmakers insist, it would capture a moment in time on a downward spiral. They feel that, better than other media, film can allow viewers to connect and empathize with other, usually voiceless people beyond our homegrown school, workplace and movie-theater mass shootings. (Released by IFC Films; not rated by MPAA.) |

||

|

© 2026 - ReelTalk Movie Reviews Website designed by Dot Pitch Studios, LLC |