|

|

||||

|

|

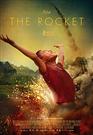

by Donald Levit  Father-son relationships, or lack or repair thereof, is a cinema staple and much a rage at present, from Nebraskans to Maoris to Japanese, and now even to for all purposes cinema industry-less Laotians. Written and directed by Kim Mordaunt and recipient of multiple awards in Oz, Berlin and New York, The Rocket is in the Southeast Asia mold of mixing fact and fable, not strictly differentiating reality from fairy tale, à la Apichatpong “Joe” Weerasethakul. This ninety-six-minute fiction grew from the also sometimes cinematographer’s Bomb Harvest, done as well with producer Sylvia Wilczynski. That 2008 feature documented the residue of UXO or unexploded ordnance of bombs, grenades, rockets, shells and landmines left over from the Secret War and other, not secret but world-ignored ones in Laos, “bombies” scavenged for scrap and, as in neighbor Cambodia, still at work killing or crippling thousands who include a large number of youngsters. In this his first full-length drama, the The climactic rocket competition brings together both documentary footage and subsequently scripted re-creation. The winning entry is that of Ahlo (a first starring part for former street kid Sitthiphon “Ki” Disamoe), making of him at once savior-hero of drought-plagued locals and the savior of his own family, which is not only allowed to stay but begged to. More, the ten-year-old gains the admiration of his despairing widowed father Toma (Sumrit Warin, to now only a stuntman in Asian action movies) and of traditional grandmother Taitok (Bunsri Yindi), who had decried him as a Jonah from the day of his birth as the only survivor of unlucky twins. Ahlo’s charming, also displaced-person companion is Kia (Loungnam Kaosainam, who initially “fought furiously” with her juvenile costar), missing her father, mother and front teeth but pledged to care for her renegade Uncle Purple (Thep Phongam, an ethnic Lao comedian-actor long popular on Thai movie and television screens). Nicknamed from his incongruous unwashed sports jacket, the grizzled drunk, James Brown freak and former CIA-recruited combatant is pariah even among migrating rural people ousted from family lands for relocation by politics and Big Business, in this particular case combining to a build a profitable dam that will flood their meager farms and dwellings. The children’s friendship is firmed by the loss of both their mothers, Ahlo’s (Mali, played by Alice Keohavong, now a Sydney resident in her first feature rôle) in an accident transporting that beloved only son’s possessions when the family of four is forced from its home. Subsidiary but there, behind the feel-good of sire and son, family, friends and tradition, lie the lingering disaster of the detritus of modern warfare and the postcolonial specter of First World “progress” in Third World countries where birthrights are sold or forced to international interests and corporations for the benefit of the already rich and politicians at home and abroad. Squarely in the foreground, nevertheless, remain the two children, the madman, the outcasts. They may well not inherit the earth, but in The Rocket they triumph, even if momentarily, because they are innocent enough to believe and act as though the impossible is possible. (Released by Kino Lorber; not rated by MPAA.) |

||

|

© 2026 - ReelTalk Movie Reviews Website designed by Dot Pitch Studios, LLC |