|

|

||||

|

|

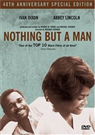

by Donald Levit  Very much a part of 1964 times they are a-changin’ yet ahead of its cinema time, Nothing but a Man won two awards at Venice and was embraced by Nouvelle Vague cinéastes and in 1993 voted into the “culturally, historically or esthetically significant” National Film Registry. In between, it languished, with no major distribution and known mainly in 16mm projections at black schools and churches. This year (2012) it was the Martin Luther King Day afternoon feature at the Queens, The crisp black and white anticipates Killer of Sheep, Charles Burnett’s 1977 student thesis film that also gathered awards and praise but bounced around at festivals and campuses in 16mm until recent 35mm theatrical release. Backed by powerful music -- this earlier one by Motown’s best, the other from the director’s own jazzy blues collection -- they are unhysterical looks at working-class African-Americans denied the American Dream. Coincidentally, Michael Roemer’s first fiction feature faced objections similar to those to Gershwin’s 1935 Porgy and Bess, which has just reopened in revised form and title. The jazz-opera-Broadway musical about Catfish Row was by two New York Jews and a white Southerner -- Sidney Poitier disowned the 1959 film version, into which contractual obligations had forced him. Jewish Roemer had been evacuated from Hitler’s It is difficult to fathom the long obscurity of the film, sincere, compassionate and daring to use (but not overuse) the N-word while favoring “boy” in the mouths of racists. Perhaps it was not sufficiently strident or political to suit activists. In a rôle turned down by Poitier, Ivan Dixon’s (also in the PB film) Duff Anderson may be “uppity” to Alabama whites, a “troublemaker” to fellow blacks, and an irreligious uneducated fool to Rev. Dawson (Stanley Greene), but he quietly refuses to back down from his human dignity. Limited by conditions, he works alongside other underpaid blacks (among them Yaphet Kotto, in his début, as Jocko) on railroad section crews, among whom the bucks take their pleasure in whiskey, women and cards. Four-year-old James Lee back in To her parents’ dismay, they marry, and she is soon happily pregnant, while, no unions allowed, Duff takes a succession of demeaning jobs (at one of which, Moses Gunn débuts as a lumber mill worker). Not that he is mouthy, but he will not scrape and bow, accept common humiliations, laugh at white’s sneering sexual innuendos about sisters. A well-meaning City Service station owner is helpless to keep him on, and fellow blacks tattle on him for remarks about their atrocious conditions. Josie is patient and knows that whites “aren’t as afraid of us [black] girls,” but, hobbled as a breadwinner, he grows despondent, distant and abusive. Her I-told-you-so father would like the socially embarrassing son-in-law gone, and Duff returns to Racism and economic deprivation are one thread, related to another, more salient one. That is the universal theme of family, husbands and wives and children, fathers and daughters, fathers and sons. Without that father and father-figure, social fabric is fractured and imperfect. Catting-around section gang laborers are surprised to learn that a calm older mate actually has a wife and two daughters to go home to. Rather a drifter himself, Duff sees the necessity of responsibility and roots as a basis for manhood. Continuity in children is the future, for which strength and family are the bedrock. His father’s gift to him is “not to do what I have done, not to end like me.” If the ending is pat, it is nevertheless the solution. (Released by Cinema V; not rated by MPAA.) |

||

|

© 2026 - ReelTalk Movie Reviews Website designed by Dot Pitch Studios, LLC |