|

|

||||

|

|

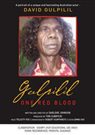

by Donald Levit  The title subject of Gulpilil: One Red Blood is an icon Down Under. But David Gulparil Gulpilil’s handsome face, toothy smile, lithe body and name are hardly recognized outside that continent homeland despite Walkabout, The Last Wave, The Right Stuff, “Crocodile” Dundee -- “you can’t take my photo, Miss, because your lens cap’s on” -- and The Tracker, Rabbit-Proof Fence and The Proposition. In small or big parts, he plays what he is -- a solitary Aboriginal pioneer like sportswomen Evonne Goolagong and Cathy Freeman -- though to countrymen he is also a TV star, didgeridoo virtuoso, dancer and teacher, and champion of his Native Australian people. The Darlene Johnson documentary is among sixty-three entries from thirty-seven countries in the four-venue 19th Annual African Diaspora International Film Festival of “films otherwise ignored . . . [since] the international Black communities continue to play a disproportionately marginal role in the art of [distributed] cinema.” Speaking at the Festival in 2001, a year before it showed Rolf de Heer’s US-undistributed The Tracker, Gulpilil himself remarked on the industry’s ignoring people of color. Minutes shy of an hour, this 2003 non-fiction credits its subject as co-collaborator. He has been such, really, in all the screen projects, as testified to by De Heer, Philip Noyce and others. Outsider directors were taken under his wing and initiated filmically into the ways of the first Australians or, as in Roeg’s Walkabout, enabled to depict the nationally disturbing idea that an Aboriginal male could arouse sexual stirrings in a Caucasian female. As on this side of the Pacific, the screen had skirted such issues by using made-up white actors to portray indigenes. Playful-serious Gulpilil is the model for part of Paul Hogan’s outback-wise Mick Dundee, from only a vest on a wiry torso to put-on spearing a fish actually killed with a rifle bullet to conning a white into stripping as unwitting protection in croc waters. There is another side, too, though one wonders how much is defensive hiding the hurt at slights without current remedy. Much is made, here on the screen and elsewhere, of his decision to live apart from Western civilization’s accoutrements of fame and fortune, in the He enjoys his neighbors, dancing at the first-ever-filmed coming-of-age circumcision ceremony, river fishing with children, or cooking and feasting. And he does point out the harmful inroads of progress, from cigarettes to ecological change. But he is most patently aware that “I am not rich,” the battered Land Cruiser needs constant TLC, promised government aid has not materialized, and structures of corrugated tin and abandoned “detour” signs lie unfinished. Brief archival footage shows the youthful subject laughing and bubbly in The film is not straight life biography, for he springs full-blown, with nothing of childhood and youth. Only one relative is identified -- who sees inspiration in his cousin’s success -- and two former lovers (one white), while the many children around him may be his or not, and the elderly woman his mother, or not. These emotional ties not explained or explored, a sense of incompleteness must remain, questions unanswered. Is Gulpilil fully realized and content; or is he, like his Tracker, keeping an inner self hidden beneath an outward rôle assumed for the conquerors? (Released by Ronin Films; not rated by MPAA.) |

||

|

© 2026 - ReelTalk Movie Reviews Website designed by Dot Pitch Studios, LLC |