|

|

||||

|

|

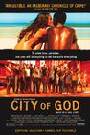

by Betty Jo Tucker  For someone like me who grew up watching so many movies featuring the Dead End Kids and the Bowery Boys, City of God offered a rude awakening. Any lingering fantasies about gang brotherhood and smart-alecky hoodlums who just want to have fun went up in smoke amid the violence exploding on screen in this disturbing film. Now I understand that gang-related crime represents a truly bloody business Ė at least in the slums of Rio de Janeiro. Paulo Linsí fact-based novel provided director Fernando Meirelles with more than enough ammunition to target the social chaos rampant in certain parts of Brazil. Hereís an issue as well as a filmmaker to be reckoned with. "A friend of mine gave me the novel along with the idea to turn the almost 700 pages into a film," says Meirelles. "I didnít give it any thought at all. I knew the book was about the beginnings of drug dealing in Rio de Janeiro, a violent story, without hope, which took place entirely inside a favela (slum area) . . . but it was the book itself that almost ran me down, asking to be adapted to film" In transferring Linsí acclaimed book to the screen, Meirelles focused his impressive cinematic eye on a group of youngsters living in Cidade de Deus (City of God), a poor Brazilian housing project built in the 60s. These kids know they have a short life expectancy. With its organized crime and drug dealing, their neighborhood has become one of the most dangerous places on earth. Such problems as poverty, rape, robbery, killings, and betrayal are commonplace and must be dealt with almost every day. The film spans a period of time from the late 60s to the early 80s, concentrating primarily on Rocket, who later finds a job as a photographer, and Liíl Dice, a lad with a terrifying vicious streak. I found it quite chilling to watch Liíl Dice transform himself into Liíl Zť, the most feared drug dealer in Rio de Janeiro. As in Rabbit-Proof Fence, much of the realism projected in City of God comes from its casting of non-professional actors. Meirelles knew he had to find a hundred young boys ranging between 12 to 19 years old, who were "sensitive, charismatic, intelligent, generous and available," so he worked with various local neighborhood and cultural groups in selecting the final candidates from an initial group of 400. While none of the cast members evoked the same "Wow" reaction I experienced watching Rabbit-Proof Fenceís Everlyn Sampi, two of them deliver excellent performances, and the rest helped make the movie completely believable to me. Leandro Firmino da Horaís portrayal of Liíl Zť ranks as one of the most realistic film "bad guys" of the past year. My skin still crawls thinking about the rage inside him. And Alexandre Rodrigues, playing the observant Rocket, effectively projects his characterís desire to be something other than a gangster or drug-dealer. Admitting he identifies with Rocket, Rodrigues explains, "I also have this dream of getting out of the favela to become a competent professional . . . Every young kidís dream around here is to say, ĎMom, Iím going to take you out of here.í" Unusual filming techniques also add to City of Godís realism. Cinematographer Cťsar Charlone claims the movie resembles documentaries he made in the early 80s. Using a camera and lighting style that shows the favela without any "adornments or feigning, " Charlone took me right into the middle of that frightening world. And now, because this is a film based on real people and events, Iím very sad. Only Rocket left me with any glimmer of hope. On DVD, City of God includes a documentary feature, News from a Personal War, which also paints a bleak picture of life and death inside Rio's drug-riddled favelas. Interviews with policemen, dealers, dwellers and children show the hopelessness of the situation. Young boys turn to dealing because it pays so well; police are the only government representatives who enter the favela -- and they are fought by the dealers. The dwellers express more respect for the dealers than the police because they can get financial help from them when needed. This unsettling documentary also highlights the important role guns play in the continuing battle between the dealers and the police. What is the answer? One interviewee suggested closing the gun factories in Switzerland, the U.S., and Russia because all the guns in the favelas come from these countries. Hmm. Although City of God and its DVD bonus feature, News from a Personal War, are not for the squeamish, both emerge as informative and effective filmmaking. (Released with English subtitles by Miramax and rated "R" for strong brutal violence, sexuality, drug content and language. Bonus features unrated.)

|

||

|

© 2026 - ReelTalk Movie Reviews Website designed by Dot Pitch Studios, LLC |