|

|

||||

|

|

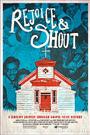

by Donald Levit  Postponed a month on account of Hurricane Irene, the Maysles Cinema “An Afternoon of Gospel” found the right place in Mount Morris Ascension Presbyterian Church in Harlem. Introducing music documentarian Don McGlynn’s 2010 Rejoice and Shout were live performances, a half-hour each from First Corinthian Baptist and the in-house choirs. The film historical survey opened with an amazing ten-year-old’s unaccompanied “Amazing Grace,” seated in a pew among her Selvy Family, who appear later on. This burst of beauty and emotion is at once followed by the first of the black-and-white photographs and, later, moving and still images of the origins and development of the subject: cotton-field hands and rural poverty leading to migration to cold northern cities and churchgoing in Sunday best. Arising in plantation and work songs, spirituals, the oratory of preaching, and the entranced speaking-in-tongues of testifying congregants, it used the call-and-response church rhythms in choral urging of a soaring lead singer. By mid-century, it was to influence, and partly become, popular music -- the Bay Area Edwin Hawkins Singers -- although holdouts like Mahalia Jackson -- shown on The Ed Sullivan Show -- refused to merge or cross over, in contrast to Sam Cooke of the Soul Stirrers, Aretha Franklin, Clyde McPhatter, Little Richard, James Brown, Solomon Burke, all except Cooke unmentioned. Not explored, either, are the ‘50s a cappella and doo-wop pop links, or the jazz riffs, for concentration is on earlier roots and evolutions. Some material is unique, as for instance 1902 minutes of the Dinwiddie Colored Quartet and, twenty years afterwards, the Utica Quartet. Loving commentary is lavished on not widely enough known “Professor” Thomas A. Dorsey, a A surprise lies in the parallels between unaccompanied barbershop quartets and the close harmony of impeccably dressed four-to-five-man black groups, their lead singer often a tenor but occasionally a falsetto like Claude Jeter of the Swan Silvertones. Fitting in here are the famous Blind Boys of Alabama, but viewers also learn of the Blind Boys of Jackson, Mississippi, both competitors forming out of training schools for the (colored) blind. This keeping feet in both worlds, bridging sacred and profane, is seen, not in various Jubilee singers, but more in the reminiscences of Willa Ward and of Mavis Staples, the latter of whom notes that “Pop” Roebuck Staples penned “Why Am I Feeling So Bad?” in the wake of Little Rock High and that Bob Dylan told her he had listened to them since he was a teenager. Clips of groups and soloists famous or forgotten are accompanied by priceless now-gone 78-record labels like Regis, Apollo, Vee-Jay, A half-hour shorter than this hundred-fifteen minutes, last year’s Soundtrack for a Revolution concerned the songs of Civil Rights, some of them in modern-day interpretations, while, restricting itself to 1955-68 in essence, managing to feel relatively complete and unified. Rejoice and Shout treats a long century and could have been more incisive and included fuller performance clips by dispensing with head interviews with scholars, historians and, in particular, with a proselytizing Smokey Robinson, all of whom, important though they may be, interrupt often and at length. The scope of McGlynn’s admirable aim would be better served by expansion into some multi-evening television special such as those recently aired on jazz and the blues. Or, conversely, tightened by trimming excess fat, one way of which would be concentrating on a few figures, as George T. Nierenberg’s twenty-nine-year-old Say Amen, Somebody does on Dorsey himself and “Mother” Willie Mae Ford Smith. (Released by Magnolia Pictures and rated "PG" for some mild thematic material and incidental smoking.) |

||

|

© 2026 - ReelTalk Movie Reviews Website designed by Dot Pitch Studios, LLC |