|

|

||||

|

|

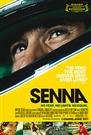

by Donald Levit  Despite Sundance and LA Film Festival Audience Awards and loud tire squeals and gear shifts, director Asif Kapadia’s documentary Senna does not catch the smells, sights and feel of Grand Prix events -- in fairness, such is hardly possible -- nor does it go deep into Ayrton Senna, an icon private enough to conduct charity work out of the spotlight. Split screen track spectacle in fan John Frankenheimer’s Grand Prix was saddled with hackneyed love stories and characters. Attempts to fictionalize Senna’s life -- by Banderas, Oliver Stone, Ridley Scott, Michael Mann -- were nixed by the Senna family, which finally cooperated with, appears in or voices over, and supplied home movies for this project by three F1 fans, co-producers James Gay-Rees and Eric Fellner and co-executive producer and writer Manish Pandey. Of equal importance was Bernie Ecclestone’s permission to cull and incorporate previously unreleased F1 archival material. Even with Brazilian and other television footage added to the full mix of fifteen thousand hours to choose from, the result does not achieve its asserted “three-act structure . . . drama, tragedy.” For Frankenheimer’s 1966 film, a 70mm camera was attached to James Garner’s car, with suspension counterpoised for balance, to enhance the two-dimensional feeling of speeds up near two hundred mph. But real 1980s-‘90s race coverage was not so good, so even from the “on-board camera” on the subject’s cars, the tracks appear slow, even for his controversial fatal accident at the 1994 San Marino G.P. There are three dovetailing threads in Senna. There is the sport itself, the teams of engineers, crew and drivers that work for automakers who vie for advantages, expertise, talent and the brand prestige of victory. (Pilots and machines are as plastered with product logos as soccer players’ jerseys.) Second are the individual rivalries that are sometimes professional and even friendly but which can ignite into spite, vitriolic attacks and, depending on point of view, dangerous tactics. Villains in the piece are two: McLaren-Honda teammate Alain Prost, multiple world champion threatened by the rising star, involved in two debated decisive crashes with Senna, and a badmouther who leaves for Williams-Renault. This Frenchman is surprisingly shown as among his rival’s pallbearers and a trustee of the Senna charitable foundation for underprivileged Brazilian youth. Jean-Marie Balestre is the other heavy, Director Kapadia is to be congratulated on not having talking heads, instead using sister Viviane, mother Neyde, F1 doctor and friend Sid Watkins, and journalists and commentators to voiceover real footage. Thus there are lots of images of Ayrton, but this third, most essential thread never cuts to any depth. His rise encounters no speed bumps: financed by a well-off A compelling story still to be told, political maneuvering within the sport and the one-upsmanship, technological tinkering, corner-cutting, negligence or cheating that possibly caused his death, are hinted at but given short shrift. Senna may appeal to those seeking non-CGI SFX speed but probably will not thrill or move the general public. (Released by Producers Distribution Agency and rated "PG-13" for some strong language and disburbing images.) |

||

|

© 2026 - ReelTalk Movie Reviews Website designed by Dot Pitch Studios, LLC |