|

|

||||

|

|

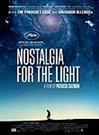

by Donald Levit  The U.S. theatrical première of Patricio Guzmán’s Nostalgia for the Light/Nostalgia de la luz follows Cannes and Toronto selections, awards, and a screening as Centerpiece of the Museum of Modern Art’s Documentary Fortnight. The subject of several upcoming major retrospectives, through an interpreter the Paris-based Chilean director-writer introduced the latter and, with German wife and co-producer Renate Sachse, answered questions afterwards, even to acting out some points. During the five years of filming and financing, the couple faced doubting television networks worldwide, and Guzmán deplores the dumbing down of that medium: “We don’t deserve this, es un escándalo.” This particular project had begun loosely about astronomy, a hobby since boyhood, but gradually came to include “all of our life, [which] comes from the past -- geological, archaeological, individual, for most of our existence is past, supported by our memory.” Strongly personal meditation including but metaphysically going beyond the auteur’s voiceover narration/observation, the more-or-less documentary is informal essay, celluloid realization of Montaigne’s 1580 “Myself am the groundwork of my book.” The small events of every situation, Guzmán’s “'dramatic atoms,’ are like words, strung together to form sentences or films,” and also parallel to the “space calcium” that eighty-year-old astronomer George Preston informs him is identical to that in one’s fingers or spine. That is, we are stardust, Emersonian cosmos in a water droplet: those desaparecidos under Pinochet and the indigenes and slaves worked to death in nineteenth-century saltpeter mines, men , women, stars, galaxies, universes or multiverses born to die and return to their origins to be reborn. Starting point is northern Sensitive young articulate astronomer Gaspar Galaz explains that light needs travel time between source and beholder, and that what Earth sees from ever-more distant reaches in space is therefore old, a blast-record from the past. But then, he adds, the delay between act and perception, thought and (re)action, is shorter but still takes a nanosecond, so that camera and microphone are actually capturing what is already past. Thus, all becomes memory, as present is borne back ceaselessly into past. Centuries of traders and llamas passing through to coastal settlements, some only to die here, have left traces for today: carvings in soft stone or mummies preserved in the bone-dry heat-and-cold to rest finally paper-wrapped in the Forensic Institute of Santiago. As group photographs of exploited miners and rows of headshots of political prisoners keep outward appearances, dead souls are preserved in the memory of the living. Former detainee Luís Henríquez traces near-obliterated names incised in the Chacabuco miners’ quarters-turned-prison and recalls astronomy lessons there and “using the stars to keep inner freedom”; another, architect Miguel, paces off cell and installation dimensions he committed to memory (after destroying each day’s sketches) so as to draw the blueprints today. And for twenty-eight years, kin, largely women, have scoured nearby scrubland for chips of bone or clothing from their loved ones still unaccounted for of the thirty-to-sixty thousand who vanished. Victoria Saavedra tells of being “reunited” with her brother José, spending a morning at home holding his found shoe with the desiccated foot still inside. Men and women of science comment, noting one theory that the bereaved should let go of the past but also that each pain is universal and yet individual, unknowable to others and to be dealt with case by case. Interspersed are the awesome colored stills of nebulae, galaxies and stars that modern technology has been bringing back. Like Walt Whitman’s word unsaid not in any dictionary, utterance, symbol, this film-essay is deliberately freewheeling in that, personal and yet bulging with ramifications, there can be no clear ending or beginning, definition or conclusion. That each and all form part of a larger whole, ever-dying only to be re-created, is one implication. The wonder, and the individual-cosmos connection, is suggested in the too-often-used device of sky- and sand-searchers amidst Tinkerbell pixie dust, motes and sparkles, a “cheap” effect, the director laughed, achieved by tossing an abandoned observatory’s dust into the air for filming. (Released by Icarus Films; not rated by MPAA.) |

||

|

© 2026 - ReelTalk Movie Reviews Website designed by Dot Pitch Studios, LLC |