|

|

||||

|

|

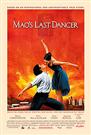

by Donald Levit  Bruce Beresford several times instances “rags to riches . . . of epic proportions” to describe biopic Mao’s Last Dancer. It is that, from ballet star Li Cunxin’s autobiography but, like the director’s repeated phrase, is also so much cliché, weighted with mediocre acting, that dance devotees will find little inspiration in the short performance sequences. The prime obstacle to realizing Australian Jan Sardi’s filmscript -- Li, second wife Mary McKendry (Australian ballerina Camilla Vergotis) and their three children live Down Under-- lay in finding a young Chinese “big ballerino” speaker of English and Mandarin available in the West. It was retired Li himself who located a perfect fit in A corollary conundrum involved getting permission to film within On the merest of chances which was not to occur until a village teacher called officials back, the boy Li (Huang Wenbin) is whisked from hardscrabble peasantry, selected from among literal millions, to wind up at a ballet school in the capital. Thus early on the theme is introduced of whether he will ever again be embraced by parents (Joan Chen and Wang Shuangbao as “Niang” and “Dia,” antiquated for “Mommy” and “Daddy”), five brothers at home and one already in state service in Lonely like others chosen to study, and the only one shown to cry at night, he is berated as physically weak by Beijing Arts Academy Teacher Gao (Gang Jiao) but encouraged by older, prescient Teacher Chan (Su Zhang). The now-teenager (Chengwu Guo) works out to build muscle and works to improve split-jump technique, and as a young man is noticed by visiting Ben Stevenson (Bruce Greenwood) and asked to be allowed to return with him for three months’ work with the Houston Ballet. Larded with flashbacks, the story is now of Li’s introduction to Western ways and rise to popular stardom. There are obligatory humorous cheap shots about acculturation and racism, but except for occasional reminders and a bad dream about the unknown fate of the family left behind, the climb is not steep, at least not successfully portrayed as such. Whatever the veto rights given Beijing censors, life there and consular representatives in this country are painted in unflattering cartoon strokes, with perhaps the fuzzy “coda [that] China is now a progressive and dynamic society” pulling the wool over their eyes. Li understandably left behind a wistful dance partner in After a trite teary “VIP” appearance at the Wortham Theater in 1986 and, three years later, an impromptu pas de deux appreciated by (Released by Samuel Goldwyn Films and ATO Pictures; rated “PG” for a brief violent image, some sensuality, language and incidental smoking.) |

||

|

© 2026 - ReelTalk Movie Reviews Website designed by Dot Pitch Studios, LLC |