|

|

||||

|

|

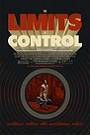

by Donald Levit  The films that Jim Jarmusch writes and directs, as well as those he acts in for others, tend toward the innovative and quirky, make use of odd cameo rôles and arresting photography, are ironic and funny though not comedies, and stately or just downright snail-slow, profound or plain pretentious. The Limits of Control follows the same trajectory, though its obvious dénouement and tiring repetitiousness may prove too much for many viewers. The attraction -- or the put-off -- is a situation that, if not extraordinary in conspiracy-agent-action cinema, promises exciting exotic story but then develops through circularity rather than linear progression. The attempt to add pseudo-philosophical depth begins even earlier, in the title taken from that of a William S. Burroughs piece about Orwellian language control (“and how we perceive things”) and a printed Symbolist Arthur Rimbaud epigraph in French about losing reassuring signposts on the descent into hell. Movies and moviemakers are referenced, by inference or specific mention, as for example Hitchcock (think dream-thriller Vertigo) and Welles’s The Lady from Shanghai, whose here-dismissed hall of mirrors climax calls up Robbe-Grillet’s chosisme theory (Last Year at Marienbad) of reality as physical and reflected like mirrors within facing mirrors. Music, too, is worked, from classical to traditional to pop to psychedelic-metal Boris compositions, for “film unfolds in your consciousness and in your emotional response in an inherently musical [way].” From a twenty-five-page treatment that bore no strict resemblance to a script, and with no storyboards, the film was allowed to grow organically during shooting, even dialogue -- more accurately, monologues -- thought up on the spot. As much as any of the name actors (including Bill Murray), none of whom except for Isaach de Bankolé appears more than fleetingly, Christopher Doyle’s photography is prominent. Round red café tables and black-and-red interiors, spiraling white Like solitary Forest Whitaker in the director-writer’s Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai, in which film he also appeared, De Bankolé is here an unnamed wordless hit man. He is advised of his assignment du jour in an impersonal Air Lumière lounge by a Creole and his interpreter (Alex Descas, Jean-François Stévenin). What happens here in seconds is what happens again and again until the unsurprising climactic act. Those who employ him protect their organization through cells of one or two individuals -- Tilda Swinton, John Hurt, Luis Tosar, Youki Kudoh, Gael García Bernal, Hiam Abbass -- presumably aware only of who is immediately above or below. Each contact opens with the same Spanish code-identification, “You don’t speak Spanish, do you?” followed by a couple often repeated pomposities about life and death and maybe a few semi-comic opinions regarding cinema or music. The hit man says nothing but is given a room key and red or blue box of wooden Le Boxeur matches containing three lines of numbers and letters, his instructions to the next drop. He in turn gives back the other box, blue or red, and orders two separate cups of espresso, swallowing the writing with one but leaving the other untouched. Tieless in one of two suits carried in his black satchel, subsequently also carrying a black guitar and case given by a contact, he sets off for whatever new destination and room, heading south, nearing the assignment. One contact reappears -- in a poster and street “abduction” -- but the rest are gone for good. Only a seduction-bent nude in black-frame eyeglasses (Paz de la Huerta) somehow crops up in his different beds, but, professionally controlled or personally empty, “no gun, no mobile phone, no sex” on the job, he affords her no more than sleep cradled on the arms he habitually folds behind his head staring up from the pillow. Still, she is the only one who lightly touches his emotions, for he brushes her cold cheek ever so briefly, justification for what he is about to do. Aside from tai chi chuan exercises in immaculate shirt and beltless trousers, he displays no likes or dislikes, pastimes or vices. Unspeaking, devoid of personality, only giving one or two slight hints of a smile, he is unfathomable and a bit creepy. Beyond the similarity of location, The Limits of Control may remind us of Antonioni’s also love-it-or-leave-it The Passenger, but while the latter’s Jack Nicholson character intrigues precisely because of a lonely journey to the unsuspected, this current film’s Lone Man is defeated by cinema context, two hours less four minutes, in this case excessive. Repetition pales after the third or fourth or fifth go-round, and the lack of revelation of depth only means that there is nothing there below the posturing. (Released by Focus Features and rated “R” for graphic nudity and some language.) |

||

|

© 2025 - ReelTalk Movie Reviews Website designed by Dot Pitch Studios, LLC |