|

|

||||

|

|

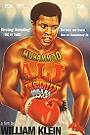

by Donald Levit  One source lists 1969 for William Klein’s Mohamed Ali, The Greatest 1964-74, indicative of the confusion within the U.S./French documentary. Although reformatting has resulted in illegible truncated big-screen subtitles, that is not the reason most everyone’s head is cut off at eyebrow level. The latter stylistic gimmick may be to deemphasize flamboyant characters in order to shift emphasis onto milieu and a larger theater, but it does not work and is in any case a distraction. Gregarious Norman Mailer is an unidentified unnoticeable few seconds in the background, ditto Floyd Patterson, Jersey Joe Walcott, Beau Jack, James J. Braddock, Joe Frazier, Stepin Fetchit, John-Paul-George-and-Ringo, and others. In contrast, 1996 Oscar documentary When We Were Kings makes good use of such commentators as Spike Lee, George Plimpton and Mailer, who analyzes the manly art of the ring as well as the irony of black pride twisted to further the promotional machinations of Don King and the political ones of Zairean military dictator Joseph Mobutu Sese Seko. Among an eclectic eighty-six entries representing forty-one countries at the 16th annual African Diaspora Film Festival, this documentary centers on three bouts, undeniably important but not the only defining Ali moments. The three fights, in fact, are not pictured at all beyond a very few grainy stills. This disappointing omission may, or may not, have been caused by difficulty or expense in obtaining rights, but the hodgepodge assemblage of collateral material does little to justify the production anyway. Imbedded in numerous printed titles, the three in question are the pair with Sonny Liston and, more than a third of the screen time, the To its unintentional credit, what Mohamed Ali does image is the world before media explosion. From the white In the section on the return match fifteen months later, one sees and learns nothing except that Boston lost money when the new champ’s emergency surgery caused a postponement and 30,000-population Lewiston, Maine, was the only venue offered for what resulted in the equally belittled first-round “phantom punch” KO. Skipping over Ali’s draft troubles, out-of-ring loss of title and livelihood, the public’s embrace of the man as more than just another athlete, and his reinstatement, loss to Frazier and road to reestablish credentials and challenge titleholder Foreman, the film turns to deteriorated color for footage around that 1974 event. With Ali defensively softer around the middle and slower with the rhymed gab, the coverage never generates electricity. Globally anticipated, the confrontation was to have been a gala return of two black fighters to their ancestral roots. The planned three days grew to six weeks for a Foreman cut to heal, so stranded media people had to fill in time. Filmmaker Klein edits in snatches of locals chanting “Ali, bumba” and obligatory but tacky dancers, training sessions in tourist hotels and the public weigh-in at the national stadium. Once again, however, there is no buildup to anything, not the (not shown) fight or a feeling for No longer ringed by controversy, dignified in disease and arguably the most recognizable and beloved public figure of the past half-century, Cassius Clay-Muhammad Ali does not emerge in Mohamed Ali, the Greatest 1964-74, neither the man nor his meaning. (Released by Grove Press; not rated by MPAA.) |

||

|

© 2025 - ReelTalk Movie Reviews Website designed by Dot Pitch Studios, LLC |