|

|

||||

|

|

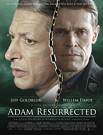

by Donald Levit  In Adam Resurrected, Jeff Goldblum transforms even his lanky befuddlement into tall dignity and ends up giving the intellectually mature performance of his career. The story trails a tortuous history from Israeli Yoram Kaniuk’s 1968 novel. Directors have been hesitant to touch the bizarre black comedy -- rumor posits an Orson Welles involvement. Paul Schrader’s 2007 filming of this highly unusual offering is an Israel-Germany co-production with no German actors. Subject aside, the story itself would have appeared to present insuperable visual obstacles. Shifts in time, of course, are not out of the cinematic ordinary, nor is the Homo sapien turned canine without precedent, as in Truffaut’s real-life The Wild Child, and the film’s Negev Seizling Institute for Therapy and Rehabilitation of traumatized concentration camp survivors is not dissimilar to the location of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, although starched nurse Gina Grey (Ayelet Zurer) is a sizzling firebomb underneath the uniform. Rather, it is the tone which is difficult, a serio-playfulness out of Latin America’s magical realism, a mix that mirrors 1920s Expressionism and later European works like Günter Grass’ The Tin Drum and (appropriate title) Dog Years, a hint of Tarsem Singh’s only partly tongue-in-cheek The Fall. Most will see Adam Resurrected as what the title intimates, the unregenerate nature of the old Adam brought back by fellow feeling to humanness after denial of self resulting from horrific experience. The film fits among other contemporary fiction works concerning individuals’ emotions -- or protective lack thereof -- during and subsequent to the 1930s and ‘40s Reich. Yet it is also insistently a Judeo-Christian parable of man’s suffering, God’s inscrutability, and the fall to despair. Schrader wrote the adapted screenplay for Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ, whose Jesus, Willem Dafoe, is now the thwarted suicide graduated to Impeccably dressed Adam stays at Ruth Edelson’s (Juliane Köhler) Tel Aviv pension, a sweet-talking 1961 alcoholic seducer hounded by the past. He is corralled and brought back to Seizling, slipping his handcuffs on the VW journey and re-entering the modern-drab facility as king again, the spielmeister all things to all people. Brilliant, a clown and conjurer and knife-thrower, the trickster out of Jewish folklore or Bellow and Singer, he controls his body to the point of profusely flowing stigmata. He can read minds, even die but be resurrected, and, declining labels “guinea pig or inmate or marvel,” he has locked away the past that begins in b&w 1926 Berlin, moves through an extermination camp, a mansion to a 1950s period-colored Haifa cemetery, and will conclude in a clumsily arranged near future, dull and “pleasant, but there is no greatness.” All this is seen through brief flashback here and there, not always triggered by specific stimuli. The handling of time, use of a reduced palette, and the hero’s occasional voiceovers, fit in and fill out the real-surreal mix that does not call unnecessary attention to its own artificiality. SPOILER ALERT Naked desert divides Dr. Nathan Gross’ (Derek Jacobi) psychiatric refuge for broken souls from the insane civilized world, past and present. In the former, Adam had been a celebrated In perverse repayment, this commandant makes the Jew his houseboy -- or housedog, forced to the canine level and company of German shepherd Rex. Miles and years from the crematorium chimney, in the desert rehab center Adam hears howls and is incensed, only to discover their source in a wolf-child, dog-boy David (Romanian amateur Tudor Rapiteanu), feral, chained and confined. Dropping his savant-holy fool rôle, Adam reverts to his camp canine creature to approach the boy, ultimately to restore, and be restored by, the child wreck of a human being. There are inconsistencies in Adam’s statements and behavior, and though he at times wills his return to serving as the patients’ leader, rabble-rouser and amanuensis, the man-boy-canine connection is what will redeem the two who have lived as dogs. Ironically, Klein’s financial juggling will bring Adam to wealth sunk in alcohol-sodden unhappiness. More ironic, the Nazi’s taunting “Is there life yet, Adam?” comes to be answered in the affirmative. More successfully than Catch-22 (Welles again, as General Dreedle), Adam Resurrected brings to the screen the neuroses arising from suppressed memory of the bestiality that (Released by Bleiberg Entertainmen and rated "R" for some disturbing behavior, sexuality, nudity and some language.) |

||

|

© 2026 - ReelTalk Movie Reviews Website designed by Dot Pitch Studios, LLC |