|

|

||||

|

|

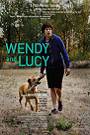

by Donald Levit  Headed open-ended towards, but not yet reaching the imagined freedom of splashier Into the Wild Northland, New York Film Festival entry Wendy and Lucy is as minimalist as its infrequent backing sounds of the heroine’s humming or a lonesome freight train whistle. Having co-scripted with Jon Raymond from his story “Train Choir,” at a NYFF Q&A director Kelly Reichardt spoke of six months’ editing in her New York City apartment, to a crisp eighty minutes -- short for feature length, hence “the long credit call”-- an inexpensive DIY that “just runs up your electricity bill, that’s all.” Related to her previous, also Northwest-set and Raymond-sourced Old Joy in the concept of life confronted anew in the moment, the film is also influenced by post-Katrina “pioneer realism,” the capacity to get somewhere else without background or credit cards when a situation turns untenable. However, the scene and theme are not the big-as-all-getout Great Pacific Northwest of male individualism, social rebels, woodsmen, loggers and Native Americans of slyly referenced Ken Kesey. Rather, her 1988 Honda Accord giving up the ghost foretold in Salt Lake City, Wendy (Michelle Williams, looking vulnerably younger than her twenty-seven calendar years) spends the screen’s few days in a depressed and distressed Portland, Oregon, of empty streets, peeling Victorian homes, recyclable-collecting homeless, and customer-less strip malls. The relevant silence of the city is in this film of silences broken once by sorry piped-in lite music and by Wendy’s unanswered cries of “Loo!” She calls her road companion, nondescript mongrel Lucy -- Reichardt’s own dog, who “loved running around the woods” for her Old Joy role -- unleashed and taken while the owner is fingerprinted at a police station after clumsy shoplifting in Jack’s supermarket. Onscreen all the time, Wendy is almost negative space. Desperate to make it on her young own without relying on anyone, she is not active but acted upon, and while her haplessness prompts others to brotherly or paternal kindness, given her situation and theirs there is little they can do. There are but few others, good-hearted yet rule-bound. The waif is, in fact, lucky. While we see none of the colorful characters Chris McCandless meets and leaves behind on his debatable journey to death in the wild, those who drift into her path could have been dangerous; but although some may be blustery or unintelligible in repetition of their four-letter expletive, her deadpan keeps her inviolate. Rarely does that façade crack, when she twice curses out of character or a demented wanderer finds her asleep in the woods or, to restrained tears at the end, her search is as frustrated as it is rewarded. The unarticulated quest is for herself, and what she runs from -- as against to -- is the small lives that must be followed by small people who in the grind do not have the luxury to act freely. Some do not, or will or can not -- clerks at the police station desk or in a supermarket -- but some few will take a chance. Father figures, auto repair shop Bill (Will Patton) gives a financial break neither accepted nor rejected, and a parking lot security guard (Walter Dalton) offers advice, his cellphone and, concealing the charity from scowling ladyfriend Holly (Holly Cundiff), crumpled fives and singles as “take it, don’t argue,” Lean like its title, Wendy and Lucy is no lo-def celebration of nature under grey skies, nor precisely a character study. A moment snatched from time, from a life coming from nowhere in particular, passing through interchangeable cities on a road map and in an agenda, and not bound for glory. These couple days in the voyage of a woman who is a child, promise no grand philosophy, neither joy, nor light, nor certitude. (Released by Oscilloscope Pictures; not rated by MPAA.) |

||

|

© 2026 - ReelTalk Movie Reviews Website designed by Dot Pitch Studios, LLC |