|

|

||||

|

|

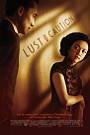

by Donald Levit  Regardless of a Venetian best picture Golden Lion, many media roundtable questions following the Of this, her feature début after experience in telefilm and on stage as actress, writer and director, the young lady from mainland One female viewer ventured that this heroine acts as she finally does because, denied the true man of her heart, she perversely transfers her physicality and then loyalty to the least likely male, precisely the one to ruin them all. Actually, motivation here is too fuzzy to say, closer to what co-screenwriter James Schamus elsewhere writes of as befitting “a woman caught up in a game of cinematic and literary mirrors.” Noting at the same roundtable that Brokeback Mountain also derives from a short story, Taiwanese now Westchester County-based director/co-producer Ang Lee revealed that his newcomer leading lady Wei had been selected from among thousands because of “a disposition that reminds me of my parents’ generation [and that] I see her as a female me, she is a kind of me. An abstract feeling.” From his male viewpoint, in equal measures clarifying and confusing the actress’ take, he added that “we never know what women get from sex, even in literature here,” but that reclusive and pessimistic authoress Chang was delving into female psychology with a backdrop of wartime Japan-occupied There are autobiographical springs from Chang’s unhappy childhood, her parents’ non-relationship, and her own first marriage to a collaborator -- she remarried during a permanent exile of forty years in Comparison will inevitably be drawn with Black Book, also about a woman -- a singer, rather than an amateur actress -- whose entrapment of her overrun nation’s enemy is colored by emotional involvement. Whereas Verhoeven’s promising premise deteriorates into spy-action cliché, the better, less conventional Lust, Caution remains true to its inner ambiguity but falls victim to that very lack of certitude. In its defense, however, on top of the resistance-fighter adopted rôles, there is difficulty with names, transliterated and varying according to the dialects and accents made much of in the dialogue, even necessitating a glossary in a just re-issued volume of the story. The height of 1942 elegance, Wei’s Mak Tai Tai [wife of Mak] enters a largely Caucasian Shanghai café, makes a coded telephone call and opens the 1938 backstory that will come around to this framing present. In the The students’ unaided plan comes to bloody naught in the wake of the Yees’ abrupt departure north. Distraught Wong/Mak Tai Tai flees, only to be enlisted again in Setting and wardrobe are relatively simple but immaculate, and combat itself distant. Mak Tai Tai/Wong Chia Chi is left -- the actress is constantly on screen -- but with no confidante to whom to turn, her churning motives are not easily if at all revealed. Less complication and length would have benefited the film, but, then, perhaps the (female) heart is unknowable. (Released by Focus Features and rated “NC-17” for some explicit sexuality.) |

||

|

© 2025 - ReelTalk Movie Reviews Website designed by Dot Pitch Studios, LLC |