|

|

||||

|

|

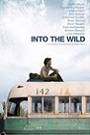

by Donald Levit  Sean Penn waited nearly ten years for the go-ahead, not from Jon Krakauer, author of Into the Wild, but from the unflatteringly depicted McCandless family the book dealt with and to whom the latter deferred. Their son Chris’s four solitary months in Alaska's wilderness of Denali and his two years spent wandering byways of the Lower Forty-Eight that preceded them, had become the basis for the 1998 bestseller, now brought to the screen in the director/coproducer’s own script. Compressed “down to a containable level of cinematic storytelling” yet in need of more trimming, the over two-hour film version presents as certainties a number of issues that the written one only speculated about, but manages to reach inside Chris (Emile Hirsch) in ways the printed non-fiction page could not. The young man’s interior -- dreams, drives and visions labeled “delusions” by some, as well as family scars -- is fleshed in passages from his reading and his sister Carine’s (Jena Malone) voiceovers (in rare integration into a film rather than as lazy exposition) plus in the faces and words of those whose paths intersected his journey of self-discovery. With didactic printed chapter headings and lots of hopping around in time and place, the story traces that overland voyage, from Emory University (with a few home movie pre-college hints) west- and northward, in seemingly random adventures but actually with a set goal both physical and spiritual: the great northern panorama, there to strip away superfluities to lay bare the essence of man and life. The twenty-two-year-old does miraculously survive real dangers -- afraid of water and a complete novice, he kayaks some serious rapids -- but those commentators who dismissed him as reckless and a fool are softened into those who noted his unpreparedness and -- moved -- supplied rubber boots, phone numbers, knit caps, collapsible fishing rods, snowshoes, money and instruction. During his “On the Road” across Innocent and transparent, the wayfarer affects these others, who instinctively want to mother him, adopt, embrace, love and protect, while his route is beyond their daring yet also their vicarious fulfillment. Krakauer’s and then Penn’s research and interviewing cannot claim to have reached certainty, including the marital redemption through suffering of parents Walt and Billie McCandless (William Hurt, Marcia Gay Harden). This is story derived from impressions after the fact and from conjecture, but lessons do emerge. Not to deny the human drive for knowledge of self and the world, or that preparation and luck may come into play, Into the Wild admires its hero’s attempt -- and romantically asserts its success ---but, unintentionally, also shows that rationality and reading are not always quite enough. Make that selective book-learning. Among Chris’s favorites, bulk and weight carried to the abandoned Fairbanks City Transport bus, figured Jack London, whose newcomer chechaquo perished for want of a match. And Thoreau, whose “wish to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life,” went a short distance -- “I have traveled much in Concord” -- not too far for visits both ways and bringing dirty laundry home to mother. Then there is Tolstoi, whose late search for Christian and family love came notably after harsh spousal treatment and thirteen children; and Pasternak, who saw happiness achieved through sharing. And, crucially, a guide to regional flora. Chris’s concentration on only parts of these books and, particularly, his invariable departure, having inspired love but ignored human yearning for commitment, might be interpreted as marks of egotism rather than spirituality. He was likely a common mixture of both, and his story, what can ever be known of the real Chris, is well served on-screen. (Released by Paramount Vantage and rated “R” for some language and nudity.) |

||

|

© 2026 - ReelTalk Movie Reviews Website designed by Dot Pitch Studios, LLC |