|

|

||||

|

|

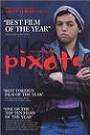

by Donald Levit  The sensation that was Pixote and the international career of its director/producer/cowriter Hector Babenco came near to never leaving the launching pad. Turned down for Cannes, though later winning Continental prizes at Biarritz and Locarno, it was presciently picked up for the Lincoln Center/Museum of Modern Art’s joint New Directors/New Films and praised by Vincent Canby and, at several pages’ worth, Pauline Kael. Reasonably compared to Buñuel’s Adding depth and following this feature is Pixote in Memoriam, introduced in person by codirector Gilberto Topczewski and filling in and updating both the original film and its participants. The 2005 documentary should not have squandered so many of its seventy-eight minutes with irrelevant head comments from three outside celebrities and, at great length, concluding pro-and-con back-and-forth on the issues of social justice surrounding the child star’s sad fate. The bright sharpness of In Memoriam insets from the 1981 feature calls attention to the unfortunate poor quality of the scratchy, faded copy now projected. But the hindsight commentary does provide invaluable from-the-horse’s-mouth about the auditions, the planning and the serendipity that went into the unexpected success; on acting in Brazil and momentary or lasting fame, its advantages and drawbacks; and on the controversial wonderful final scene between that child and the whore-lover-mother, made up on the spot and not, as one imagined, scripted after Rosasharn’s act in The Grapes of Wrath. Pixote’s subtitle, A lei do mais franco, “The Law of the Weakest,” hints at Social Darwinism turned on its head, as young delinquents from São Paulo favela Diadema are rounded up when police need the usual suspects for a street murder. Babenco’s personal presentation of statistics, of the slum itself and of his youngest star, would give what follows a documentary feel, though interviews two decades later with the mostly non-professional participants indicate that, unlike the deprived fictional characters, they themselves were largely from comfortable families. The adolescents netted by police are introduced, with names and ages read out. Attention centers on angelic-faced ten-year-old Pixote (Fernando Ramos da Silva, whose real broken foot in a cast was simply incorporated), smallest, youngest and most innocent among the several who gravitate together in Febem, the reformatory to which they are sent, underage and not liable to prosecution. On-site director Sapatos Brancos (Jardel Filho) looks like Nick Nolte and is less demonized than expected under circumstances determined by politics, graft, payoffs, corruption, police and inmate brutality, fear, media lies, sodomy, inadequate medical attention. Fumaça’s (Zenildo Oliveira Santos) death from a beating is witnessed by Pixote, in the infirmary from sniffing glue but who during the subsequent riot escapes with effeminate gay Lilica (Jorge Julião), “her” boyfriend-to-be Dito (Gilberto Moura) and Chico (Edilson Lino), leaving behind leg-braced singer Roberto “Silverfoot” Pie de Plata (Israel Feres David). Through Lilica’s old lover Cristal (Tony Tornado), they get heroin to deliver in Rio but are naïvely bilked by a peroxided bar girl (Elke Maravilha, as Debora), and blood is shed (after a difficult time convincing Ramos da Silva that the knife was a harmless prop). Scripted from the José Louzeiro book Infância dos mortos/Childhood of the Dead, the picaresque plot takes the three surviving boys into buying a pistol and part interest in street prostitute Sueli (a magnificent Marília Pêra, one of the film’s few professionals and, she notes, the only member of a family of generations of actors to make a living at it). In these rough surroundings the boys are innocents, shocked by Sueli’s recent abortion, and the woman becomes their friend, accomplice, mother, lover and instructor in the Murphy game of robbing drunk johns. The game turns rougher than planned, however, deep needs and taboos surface, and the child that is Pixote tightropes his way along rails into distance and future. Pixote aspires to a taste of non-committal “scientific” methods of post-war Italian cinema, but Babenco’s in-person opening remarks betray the decided social slant of the then-thirty-five-year-old. It is, rather, two-and-a-half decades later, in Pixote in Memoriam, that he distances himself from the character Pixote and, especially, the actor Ramos de Silva. It is that later stance that, depending on the viewer, must be disturbing. (Released by Unifilms; not rated by MPAA.) |

||

|

© 2026 - ReelTalk Movie Reviews Website designed by Dot Pitch Studios, LLC |