|

|

||||

|

|

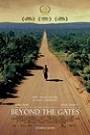

by Donald Levit  Joining Don Cheadle’s standout character portrayal in Hotel Rwanda and Forest Whitaker’s as Uganda’s Idi Amin, is John Hurt’s as Father Christopher in Beyond the Gates, far the most involving picture about the quarter-year slaughter of a million and displacement of hundreds of thousands in Africa. Hurt splits top billing with Hugh Dancy as Joe Connor, idealistic recently arrived teacher at his Ecole Technique Officielle. Twice the young man’s age, with half his life spent as a priest among Africans--actor Hurt’s “family is steeped in missionaries, monks, Catholicism, conversions, priests” -- Christopher must gently bail his new worker out of a doctrinal classroom knot and smooth the way for a final agonizing choice. Drawn into realization of the beast that surfaces in man, the drive to stand apart and to protect one’s own kind, and the primal fear of death and urge for self-preservation, Dancy’s rôle in awakening from boyish wonder to horrified helplessness (at external and internal events) requires a clamped jaw and eyes that look straight ahead while indicating seething emotion. Indeed, it is the running- and religion-obsessed student Marie (Clare-Hope Ashitey) who has a crush on Joe, who asks the questions that at the time are beyond him, and who, in a coda five years later on the green playing fields of England, is wise enough to advance to him the meaning, purpose and dedication that the priest-missionary had momentarily lost and then found again but was prevented from articulating. Some viewers at the screening I attended derided this overtone of faith, more, it seemed, on aesthetic principle than as a perspective on the otherwise unimaginable “things too wonderful for me, which I knew not . . . understood not.” Moreover, a coordinator for the country’s Survivors Fund has asserted that in no case did one single white refuse evacuation, just as President Paul Kagame (a Tutsi whose invading rebel army ended the mass killings) spotted “falsehoods” in Hotel Rwanda, while similar controversy of “serious inaccuracies and omissions” surrounds Sometimes in April, Raoul Peck’s television film. Documentary and fact-inspired fiction alike have their slants, though at times one instinctively senses a fidelity to individual and group truth, as, for example, in Ian Gabriel’s incisive but ignored Forgiveness, on the Desmond Tutu Truth and Reconciliation Commission Hearings, as compared with the sappy love story-driven vehicle that was John Boorman’s In My Country. In the screenplay deriving from a story cowritten by (coproducer) David Belton about his live BBC coverage of the events, and filmed at the actual school, the good shepherd stays, to be martyred, with his flock. While other characters are composite portraits, the “inspiration” was Vjeko Curic, a Bosnian priest who sheltered the correspondent and his team and was one of only two foreign clerics who stayed the course. Whichever of the diametrically opposed claims is correct, the “feel” rings true to the human heart and the result is moving, although not because of the strewn corpses and certainly not the cheap-shot television insert on the definition of “genocide.” From Father Christopher admits thousands of terrified civilians into the limited facilities and keeps school and chapel functioning as normally as possible. European whites figure among the refugees, including burnt-out television reporter Rachel (Nicola Walker) -- who mothers Joe, thus avoiding romance cliché -- and her photographer Mark (Jack Pierce), and when the Security Council refuses to investigate or recognize genocide and ten of Conveniently made the son of parents who helped Jews evade the Nazis, Delon is anguished but adamant that he and the men under him follow orders, returning fire solely in self-defense. In an easy scene explaining the working title of Shooting Dogs as well as standing for foreign attitudes, Delon is berated by obscenely angry Christopher for considering shooting at dogs devouring bodies but not at the bloody-minded mob outside. In sequences recalling 1975 Inaccuracies there surely are here. This is dramatization, but the best yet to come out of that inexcusable situation. Employing survivors among its crew, Beyond the Gates is honest and moving. Attending the première last year in (Released by IFC Films; not rated by MPAA.) |

||

|

© 2026 - ReelTalk Movie Reviews Website designed by Dot Pitch Studios, LLC |