|

|

||||

|

|

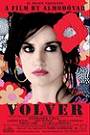

by Donald Levit  Pedro Almodóvar’s Volver is not a departure, an about-face, or an indication that his work to come will look to the past rather than to the future. Undeniably his country’s one-name superstar -- “Viva Pedro” is the theme of one current retrospective -- the director managed to overshadow actress Penelope Cruz and executive-producer brother Agustín Almodóvar at the press conference while at the same time appearing either more tentative (relatively speaking) or else serene “such as I haven’t felt for a long time.” He sees his sixteen films as “a path, a chain in a way, a trajectory, a kind of logic to which they’re moving.” For Almodóvar, now fifty-five and become something of a fixture on the grand stage that is Lincoln Center’s New York Film Festival, volver, “to come/go back,” does not mean nostalgia, but, instead, “squarely” assessing the past on having recognized one’s own ageing and mortality. At around half a century, he is looking at childhood with different eyes, “I can think of the woman who raised me” and of the “reactionary, machista, austere, . . . [anti-]sensuality town, the last place you’d want to live,” where he did in fact spend his first eight years. Its title also from that of a famous sensual tango, the film is a laying to rest emotional and physical ghosts in a place where people sweep and water their own future graves as well as those of the restless or sleeping dead, and also a coming to grips with the present (and, so, the future) by bringing forth both the black and white of what has gone before, the hushed dark deeds and the loving sacrifice. Offered as “dramatic comedy,” this newest effort features the intricate surprising turns audiences have come to expect, but goes easy on sex and the trademark loveable kooks one either relishes or has grown tired of. One of Almodóvar’s more subdued works, it mixes genres but in the end achieves neither serious drama nor serious comedy. The latter, present in one-liners here and there, is meant to take off with the appearance of Carmen Maura, wasted as the spirit of mother Irene, complete with suitcase, white knee-highs and disheveled salt-and-pepper hair in the trunk of daughter Sole’s (Lola Dueñas) car and later under her bed. The potential “dramatic” does not work, either, hinting at great undercurrents but, though eventually uncovering secrets, senility, murder, child neglect, incest, apparent parricide and terminal cancer, undermined by lack of firm tone and the drift toward easy laughs. There are no villainesses in this nearly all-woman film, just mothers and daughters who have made mistakes. Driving regularly from the city to visit half-blind dotty Aunt Paula (Chus Lampreave) in the village house filled with haunting family memories, are abandoned wife Sole, who scrapes by with an unlicensed hairdressing salon in her flat, and her sister Raimunda (Cruz), a cleaning woman at the airport supporting a lout of a husband (Antonio de le Torre, as Paco) and their thirteen-year-old Paula (Yohana Cobo). In the SPOILER ALERT The key proves doubly useful. Daughter Paula knifes Paco to death when, claiming not to be her father, he tries to rape her; the freezer will serve as cold storage until the body can be removed. (Spanish slang for a corpse is fiambre, cold cuts.) Secondly, lucking onto a thirty-man film crew in need of daily eats and a bang-up farewell dinner, Raimunda begs and borrows friends’ money, food and help in miraculously setting up a profitable business in the empty restaurant. Love is even hinted at, in a crew head who often eyes her, but this is simply dropped and forgotten. Not forgotten is the past, for with Auntie’s death mother Irene’s fleshly ghost moves in with Sole and even helps out as a “non-Spanish-speaking” illegal “Russian.” Agustina shows up, too, for medical tests and a reality show TV appearance to broadcast the search for her mother, and finally to ask Raimunda’s help in that search. Raimunda has mother issues of her own, with the one she bitterly felt abandoned her and with the secret of her own daughter. Such twisting turnings are the stuff of Almodóvar, and in this case it will be Irene alone who holds the key to unlock the turbulent past and bring peace and reconciliation to the here and now. It is personally good that the director/screenwriter feels he has faced and come to terms with his own. For once he enjoyed the shoot, “didn’t suffer at all [or] have the feeling of being on the edge of the abyss.” All men need what he calls his “painless mourning and goodbye to something (my youth?).” But the creator in him seems to need that restless angst, as well -- for the result, Volver, is Pedro in a minor key. (Released by Sony Pictures Classics and rated "R" for some sexual content and language.) |

||

|

© 2026 - ReelTalk Movie Reviews Website designed by Dot Pitch Studios, LLC |