|

|

||||

|

|

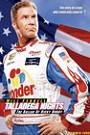

by Jeffrey Chen  I think the reason why Talladega Nights: The Ballad of Ricky Bobby works so well as a comedy is because its subject can't defend itself. This Will Ferrell vehicle, directed by writing partner Adam McKay, is essentially chucking javelins at good ol' American redneckery. And seriously, have you ever seen an indignant redneck? No, and I'll tell you why: no one thinks he or she is a redneck. Ferrell and McKay, whose last collaboration was Anchorman: The Legend of Ron Burgundy, have applied their Anchorman story formula -- a man in a position of fame suddenly faced with a challenge to the very narrow core of his being and destroyed by it -- to the world of NASCAR racing. For some reason or another, NASCAR racing has come to be known as a redneck-enjoyed pastime. I'm showing my ignorance here -- I knew little about this world years ago, and in my limited exposure to it, the media has enforced upon me the idea that NASCAR is for folks who drink beer and speak in a drawl. I have no idea what that world is really like and can barely believe it exists as portrayed. I'll bet people living that lifestyle can't believe it either, but when they see it on TV, as when some famous comedian pokes fun at it, they recognize something -- maybe those caricatures remind them of someone they know. But caricatures they are, and they're here for the roasting. In Talladega Nights, its cast of delightfully self-absorbed and simple-minded characters represent every boorish stereotype of flyover-state America, and we all believe we know better than to be like that. Ignorant of culture. Scared of the foreign. Negligent of responsibility. And yet obsessed with being the best. Ferrell and McKay aren't as dumb as the characters they write -- they lampoon these people not in a mean-spirited way, but rather in a method that makes them look pathetic (in both senses of the word). They know enough not to paint their protagonist, NASCAR champion Ricky Bobby (Ferrell), as irredeemably stupid or callously cruel -- he's a vessel of that special brand of childlike male insecurity that's become the fallback for many of today's successful movie comedy writers, but he means well enough and displays hope for growth. He's challenged by, of all things, a gay French racer (Sacha Baron Cohen of "Ali G" fame), a hilarious creation of pure exaggeration who, nonetheless, is never asked to sacrifice his self-perceived dignity for the sake of the plot. Ricky responds so poorly to this unfamiliar person, who in addition actually drives better than he does, that he's traumatized, and there you have it in a nutshell: Americans like Ricky are a lot of bluster masking a huge fear of impotence. And that's funny. Talladega Nights isn't a pitch perfect presentation of its ideas because it doesn't dig deeper than it needs to -- to go any further would be to truly study how general and willful ignorance harms society no matter how much of it comes from people who are capable of compassion and justified pride. But then we might start crying instead of continuing to laugh. The movie goes just far enough to give us comedy that relieves us; there's just enough truth in it to make the humor genuine and not condescending. The actors are given room to stretch their comic muscles, and the whole thing from beginning to end reveals far more unifying structure than Anchorman had. And, in making fun of what it does, the film gives viewers comfort in knowing that, if they're laughing at it for all the right reasons, they must surely be above what they might refer to as a redneck. (Released by Columbia Pictures and rated "PG-13" for crude and sexual humor, language, drug references and brief comic violence.) Review also posted at www.windowtothemovies.com. |

||

|

© 2026 - ReelTalk Movie Reviews Website designed by Dot Pitch Studios, LLC |