|

|

||||

|

|

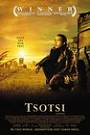

by Jeffrey Chen  Savvy viewers will know exactly where Tsotsi is headed the moment the title character discovers the car he's stolen carries a baby in the back seat. Previous to this, we were given an expeditious introduction to Tsotsi's (Presley Chweneyagae) seemingly merciless gangster youth persona. Emerging from the shantytowns just outside of Johannesburg, South Africa, he commits a heinous act during a subway mugging; later, when one of his followers protests, he replies with furious violence. The carjacking scene is just as unsettling, but then he discovers the baby. This isn't Alex of A Clockwork Orange here -- our protagonist may want to give the appearance of being heartless, but the script is stacked against him. Burdened with an embittered past, he's now ripe for a path to redemption. The baby doesn't necessarily turn him into a softie -- it's just that he can't bring himself to leave it to its fate, so his confused attempts to take care of it eventually lead him to slowly unearth his own humanity. The arc is touching, but the story seems too easy and its themes commonplace. We're never quite convinced that Tsotsi's transformation will be challenging. Maybe it's in Chweneyagae's face -- even as he scowls and threatens others with his gun, his young countenance conveys an under-the-surface angelic quality we know will eventually come to the fore. To his credit, Chweneyagae gives a head-turning, dedicated performance, and if we were meant to be able to detect the human being inside the monster, then he's done more than his job. However, this only serves to make his fate in the movie feel as inevitable as it turns out to be. More likely, the flaws lie in Tsotsi's writing. Adapted by director Gavin Hood from a book by Athol Fugard, Tsotsi's character in this film version never feels as complex as he ought to. He's given a troubled past that includes one depicted trauma. His environment is shown to be poor and rundown, thus leading him to a life of crime, but nothing about it gives evidence to reinforce his particularly brutal behavior. That behavior then seems device-like, something the movie needs to kickstart its story toward its humane point-of-view that no one is irredeemable. In other words, at first the movie aims to disturb, but only to serve the purpose of being able to comfort the viewer in the end. Thus, the characterization lacks depth -- Tsotsi becomes a model of a young criminal just waiting to be reformed. Early comparisons of Tsotsi have been made to City of God, likely because of their similar gritty styles and depictions of youth gangs in a poor third-world economic landscape. But the comparison is unfavorable because of the two films' different goals. City of God has no interest in reforming its characters -- the bad kids largely stay bad, some decent kids get dragged down, and its observer-protagonist was good from the beginning. It was an unapologetic snapshot of an unimaginable slice of life, which is what made its horrific impact so strong. Tsotsi, on the other hand, feels like an idealist's fairy tale. It contains hope -- never a bad element -- but it's presented as a spun hope, one which we have little doubt will positively affect the title character's destiny. (Released by Miramax and rated "R" for language and some strong violent content.) Review also posted at www.windowtothemovies.com. |

||

|

© 2026 - ReelTalk Movie Reviews Website designed by Dot Pitch Studios, LLC |