|

|

||||

|

|

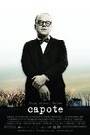

by Donald Levit  Though he made a fetish of rubbing faces in his own loveless, sad childhood, the once towering writer-personality Truman Capote went from the get-go for the jugular of celebrity -- the fey blond divan photo on, and the theme of, his first book was a calculated career move. Its title indicative of that monomaniacal pursuit, documentarist Bennett Miller’s Capote examines the precious writer of stories, novels, plays and films a dozen years after that start, at what was to turn out his triumph as artist-slash-public figure at the same moment that it marked the beginning of his creative demise. Immediately after screenings at the Toronto International and New York Film Festivals, the film opens September 30, on what would have been the author’s eighty-first birthday, and begs for consideration from two independent angles, only the second of which falls within the critical province. First, and outside that area, is the action within which the central concern arises, that is, the murders of the Clutter family of four in a tiny farm town, the arrest and extradition of two suspects, their trial and sentencing. To try out his theory that techniques of fiction in the service of actual fact could equal or surpass the traditional novel, Capote wrangles an on-location article assignment from The New Yorker. Once there, however, his ambition grows into a book, its subject the clash of sheltered The success of In Cold Blood, six years in the writing and the inspiration for a theatrical as well as a television film, affected the course of American writing and journalism and thrust its willing author further into the beautiful people spotlight he courted and helped create. Not widely known to two younger generations, the episode is sure to become revived in the public’s awareness, with sales of the book to take off once again. Even with, perhaps because of, its subject’s cooperation, Gerald Clarke’s book Capote took over twice as long to write and, augmented with the killers’ letters given him by the author, is the principal source for Miller’s friend Dan Futterman’s first screenplay. With dialogue reflecting “almost word for word” those forty-odd letters, the understatedly objective film would be what one might term “non-fiction fable.” Accompanied by childhood friend Nelle Harper Lee (Catherine Keener), Capote (Philip Seymour Hoffman) trains to The story cannot be told, the novel written, until the final act is staged on the gallows at Even Lee’s considerable one-novel success with To Kill a Mockingbird is not given much notice. All eyes are on Capote, as, for example, not once but twice, he bald-facedly lies to pathetic Perry. Abruptly cutting back and forth between plain But just as Gore Vidal saw Capote’s having “made lying an art . . . even when it is inconvenient,” so, too, does Capote the film claim more than is there. At the center of this treatment as well as its human subject, there is a coldness around the heart which, intentional in both cases, distances them from the sympathy of experience. (Released by Sony Pictures Classics and rated "R" for some violent images and brief strong language.) |

||

|

© 2026 - ReelTalk Movie Reviews Website designed by Dot Pitch Studios, LLC |