|

|

||||

|

|

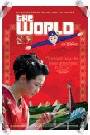

by Donald Levit  The World surely must be a bitter tongue-in-cheek take on the Its motto “Why Bother Leaving Beijing, When You Can See the World,” the hundred-fifteen-acre theme park has its malls and theaters, its reproduced scale-model Leaning Tower and Vatican, Great Pyramid of Cheops (two thousand soap-bar-size marble bricks), St. Mark’s Square and Red Square (five million domino-like red pieces), London Bridge, hundred-eight-meter-high Eiffel Tower, Wooden Pagoda, Statue of Liberty, Manhattan skyscrapers (complete with WTC), Venus de Milo and David statues, children’s fairyland, laser shows, gardens, train, boats, horses, monorail, uniformed employees and costumed showgirls. Vegas, Atlantic City, Mohegan Sun, Anaheim and Orlando, Paris, London, Rome, San Juan, Macao, Bangkok -- and Beijing. Painter-novelist-filmmaker Jia’s 1997-2002 features dealt with dusty isolated rural Fleeing the deadly dullness of the northern Shanxi province of the earlier features, Jia’s protagonists make it to the big city in this one, only to wind up working and virtually existing in “the surreal become reality” Epcot East. Love and relative fulfillment await some, sorrow and death-in-life or real death others, and even those who, like Russian Anna (Alla Chtcherbokova), appear to escape to a bright semi-foreign world, are destined not to. In this most ghastly polluted of China’s eight of the world’s ten most contaminated urban areas, skies are featureless industrial grey-white. In glitzy getups of make-believe Egyptians or Arabs or black Africans or geishas, characters live indoors, alternately ill-illuminated or garishly overlit by bleaching yellow spots. Inserted video game-quality cell-phone text-messaging images merge with, introduce or bridge episodes of these virtual lives carried on in hopes of money or fame or love, where even the out-of-doors is a Never-Neverland of replicas of a cultured lost past. Lovely Tao (Zhao Tao) is above the common chorine but still after all only a dancer in the Park after three years; her ex-boyfriend Liang (Liang Jingdong) passes through, on the way to Mongolia, and meets her current beau Taisheng (Chen Taishen), a Park security guard also from Fenyang. The latter is honest with his women, advising them to trust no one, himself included, and in this culturally and legally conservative society Tao refuses to have sex with him. Deep down, she wants marriage, a desire later reinforced when pouty fellow dancer Wie (Jing Jue) lands her possessive performer Niu (Jiang Zhongwei). Many other personalities enter and exit the mosaic, but there you basically have it. Not by any means a rogue, Taisheng is honest, loyal to fellow villagers who seek his help, good-hearted but simply not ready for commitment. As a favor to card-playing friend Song, he accompanies clothing designer Qun (Huang Yiqun) on a six-hour bus trip to deliver cash to her broke gambler brother Bing. Bob-haired Qun’s husband has lived in Europe for years -- the real Europe -- and soon she and the guard are lovers, though realistic about each other’s significant other. Tao has rejected a businessman’s advances baited with a trip to Hong Kong but (in a text message) discovers her boyfriend’s liaison. Qun manages to get out, a fellow townsman is killed on a construction site and his stunned peasant family helped out by Taisheng, other couples marry or don’t marry, sexual favors gain a promotion, and broken-hearted Tao sulks. Unless the black-screen voice-over final sentence is to be read as a threat of truly everlasting revenge, the ending is unsatisfyingly abrupt and tacked-on. But it is late, anyway, for at two-and-a-third hours, The World lingers too long. The theme is hammered home more than often enough, there are too many inessential subplots and parallels, and, not used to Asian length, American audiences will tire. Less would have been more. (Released by Zeitgeist Films; not rated by MPAA.) |

||

|

© 2026 - ReelTalk Movie Reviews Website designed by Dot Pitch Studios, LLC |