|

|

||||

|

|

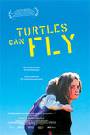

by Donald Levit  Effective but confusing, was one woman’s post-screening verdict about Turtles Can Fly. Moving it certainly is, yet both her adjectives are accurate, as shown by some little disagreement about the baby son or, in two or three minds, younger brother. And then an African-American lady’s rage about rape as a weapon of war only rose higher when it was observed that, right here at home, barely pubescent girls resume fifth or sixth grade after giving birth. Only dirty terrorists do such things, she fumed, not Americans. Maybe, but she, too, was confused and had missed the point, for, although there, the multiple violation -- introduced darkly and late, in fleet flashback -- is but one aspect of a whole fabric of blighted, crippled lives; as for the clean-uniformed, equipped and impersonally presented GIs as liberating bringers of freedom, the film closes with the central character’s turning his back on them and exiting screen left. In director-producer Bahman Ghobadi’s view, in this Iraqi Kurdistan village at the time of Saddam Hussein’s ouster, President Bush as well as the deposed leader and “any other dictators and fascists, nothing but monsters,” leave little to choose among them; they are “media stars” all, while “nobody mentioned the Iraqi people, [who here] play the leading parts.” In his self-financed, small-crew third feature, Ghobadi uses non-professionals, because “it’s too early as yet to speak of a Kurdish cinema” or for this new foreign art form to have produced national actors. For its charged political-humanitarian context, the filmmaker relies on story, adroitly assembling “a sort of collage [so as to] remain consistent for the audience.” Specifically, events focus around manipulative but good-natured thirteen-year-old Kak Satellite (Soran Ebrahim) and, more difficult because she is so closed, the haunting-faced Agrin (Avaz Latif), for whom he falls. Initially, there is comedy, as bumbling farmers partially follow Satellite’s know-it-all instructions to set up dishes and antennae with which to capture TV news. That the networks themselves are part of corporate interest groups, and that their consumer-trash programming is largely prohibited and in unintelligible American English, is not lost. Fuzz on his upper lip, wearing thick glasses, riding a souped-up bicycle and sporting jeans, floppy sweatshirt and reversed fatigue-baseball cap, and master of set phrases such as, “How are you, hello, Mr,” Satellite translates any and all news as “It will rain tomorrow . . . a code.” Piece by piece, the terrible situation emerges in this poor quagmire of a place now divided by barbed-wire boundaries and populated by tented refugees. The barren, rocky area is honeycombed with unexploded antipersonnel mines. Living amidst discarded military equipment, the gaggle of children who look to Satellite as their leader, harvest these left-over explosives for the dinars they will fetch in a nearby city market, where every sort of weapon is openly for sale, those of American and Italian manufacture being particularly prized. Together with random automatic fire, the dangerous trade leaves its horrible mark. Disfigured and scarred, missing arms or legs, many get around on crutches, including Satellite’s surprisingly nimble lieutenant Pasheo (Saddam Hossein Feysal). Using his feet as hands and his mouth to disarm mines is Agrin’s strange brother Hengov (Hiresh Feysal Rahman), who takes care of Rega (Abdol Rahman Karim), the three-year-old who in turn addresses sister Agrin as “Mummy” and whom Agrin carries on her back but love-hates so intensely that she wants to abandon or destroy him. Terrifying yet beautiful in stark, shaky cinematic effect, brief flashes poise troubled Agrin on the edge of a precipice, and Hengov himself has a power to see into the future in intermittent visions that are reliable compared to the inanities of CNN’s eagerly anticipated disembodied heads. With innocent yearning, hero Satellite is attracted to the mysterious girl and exhibits a tentative selfless gallantry, while she hesitates and then plunges away. The film’s ultimately tragic sphere is of children rather than of adults. Their elders are pompously useless and lost or else deadly effective, and unfortunately it is they who control events and interpret them to the world outside. There is no out, no happy resolution: clairvoyance is not needed to see the unrelieved bleakness of the past, the present and the future. Suffer the children. (Released by IFC Films; not rated by MPAA.) |

||

|

© 2026 - ReelTalk Movie Reviews Website designed by Dot Pitch Studios, LLC |