|

|

||||

|

|

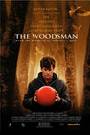

by Donald Levit  Back before films got too long and costly for double features, someone returned bewailing, “Whatever happened to Walt Disney? You go to the movies to be entertained, and you come out feeling like killing yourself.” Top billing on the dual downer had been Wyler’s second go at Lillian Hellman’s The Children’s Hour, not so effective as his earlier These Three. Undeservedly ignored, the poignant B companion piece was The Mark, in which Stuart Whitman’s attempt to rekindle a life is shattered by revelations of past jail time for child molesting. Lesbian love is today less shocking than then, but the latter crime remains taboo, its imprisoned perpetrators still ostracized and brutalized by fellow inmates. That The Woodsman tackles the theme is a step in the direction of airing and dealing with a feared perversion seemingly grown endemic. That the film ultimately sidesteps the issues raised in favor of a “happy” ending, however, is another matter. For her first feature, director and recent film-school graduate Nicole Kassell also did the script with Steven Fechter, whose play of the same name had been on her mind since 2000. Aside from adding subplot characters like sexually attracted but vindictive coworker Mary-Kay (hip-hopper Eve), their essential dilemma was to avoid the weight of verbiage yet, like a psychiatrist, open onscreen the inner world of a scared, highly private protagonist. The Mark and The Woodsman cover similar territory, though to different ends. The earlier, British film resorted to a nosey reporter and an eccentric psychiatrist (Rod Steiger) but mainly intrusive flashbacks to visualize the parolee’s mother-dominated past. The current film has its probing to the point of prurience Dr. Rosen (Michael Shannon), who uncovers no more than that the ex- and questionably future offender liked to lie down with younger sister Annette and smell her hair. With its “Save the Children” murals, a grainy City of Brotherly Love is the unnamed urban setting into which, says a computer screen, forty-five-year-old Walter Rossworth (Kevin Bacon) is conditionally released. “The only landlady willing to take my money” rents him apartment number five, with a window view of children arriving at a schoolyard and the young blonde man “I call Candy” (Kevin Rice) sizing up the boys and choosing his victim. Silent Walter preferred girls but never hurt the Walter goes back to a former lumberyard job, at which he is literally picked up and bedded by that female forklift driver, who “see[s] something in you, something good,” claims not to be easily shocked, and was herself sexually abused by three older brothers. Jaws tight below guarded eyes, the ex-con never opens up about twelve years’ incarceration and is hesitant with this would-be girlfriend, with the brother-in-law (Benjamin Bratt as Carlos) who too cheerfully visits but is protective of wife Annette and their ten-year-old Carla, and with Police Sergeant Lucas (Mos Def), a mixture of homey knowledge and thinly controlled rage against killer pederasts. Reaching for a ‘70s spareness and playing with its audience -- though others’ screening reactions were favorable -- the film offers no reason for Walter’s supposedly heroic about-face, a moment of self-control with bird-watching Robin (Hannah Pilkes), another ten-year-old he has stalked for days and whose sad story he knows from experience. So little is revealed about the hero that an end-shot move rings ominous and empty. In fact, there is fine unintentional irony in the very gratuitous explanation for the title itself. Little Red Riding Hood is dragged in for the woodsman (“among other things, a kind of policeman,” notes one scholar) who kills and scissors open the bad wolf to free the unharmed girl. So in the familiar Grimm brothers’ tale, derived from Tieck, which was, however, but a sweetened version of “Mother Goose” Perrault’s 1697 cautionary folktale, in which, sans rescuer, the “naive bourgeois girl pays for her stupidity and is violated in the end.” (Released by Newmarket and rated "R" for sexuality, disturbing behavior and language .) |

||

|

© 2025 - ReelTalk Movie Reviews Website designed by Dot Pitch Studios, LLC |