|

|

||||

|

|

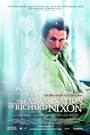

by Donald Levit  Princip, Zangara, Metesky, D. B. Cooper, Abu Kamal, et al. are unremembered, their delusions of fame, fortune or justice not even footnoted by fickle history. Given the nature of the man’s demons, equally ironic is the case of Sam Bicke, “who was here . . . and they can never forget me.” While speaking directly to post-9/11 concerns, his tale is chilling in being but one of those of armies of others whose tottering “differences” are easily nudged to the dark side by the world’s inequalities and quirks. Well before the Commentators will jump to parallels to De Niro’s Travis Bickle, which, invoking Willie Loman, instead, the director denies and points out that the sole “true name (albeit spelled differently)” is actually Bicke. Others may refer to one-note vigilante Death Wish, but a closer story is that of Michael Douglas’ also estranged geek husband, “D-FENS,” scary to some in Falling Down, sympathetic to others. Wrinkly, jelly-bellied, shrunken from No more ridiculous than hula hoops, pet rocks, pre-torn designer jeans or Tiny Tim, this hero’s brainstorms are ideas whose time has not, and may never, come -- a traveling red tire-mobile, truth in sales, renaming the Black Panthers “zebras” to attract whites -- and he is buffeted and spirals downward, to background bombardment from news and advertising. If the film uses the Cadillac symbol too often -- “convey it once, if the [audience] misses it -- let it go, don’t repeat,” was Scott Fitzgerald’s advice -- still it does conjure up the television frenzy of consumption alongside war and scandal enveloping the latter days of the Nixon presidency. In just about every shot, if only peripherally or looking with his eyes at others, the camera calls us to Bicke. Close-ups are reserved for him, and while Penn tends to overdo the pleading hangdog look, the viewer is drawn into the Milquetoast’s seeking, feels his blows, and believes at least his all-too-human turning to find those who have betrayed not only him, but the entire nation and its priorities. His path decided, he will send out voice tapes to figures like “pure honest” musician Leonard Bernstein, and though nerve fails him with Jack Jones, it is steeled for the family dog or Delta Flight 523 out of Visual backgrounds rendered unimportant and garish Naugahyde colors blunted, it comes down to the man’s disintegration. With no support system in family, workplace or synagogue -- though why fed-up Julius’ religion is even brought in, is a puzzle -- he is a symptom and, it seems, an individual often repeated nowadays. The Assassination of Richard Nixon depicts a dilemma by flashbacking to its origins and, prescient like overlooked The Siege, moves us with the roots of unpleasant realities. (Released by THINKFilm and rated "R" for language and a scene of graphic violence.) |

||

|

© 2026 - ReelTalk Movie Reviews Website designed by Dot Pitch Studios, LLC |